This post was initially included on Hakai Magazine, an online publication about science and society in seaside communities. Learn more stories like this at hakaimagazine.com.

Nestled in the heart of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University originates the aura of a vast cabinet of interests. Its neoclassical exterior is covered in natural themes– entrances flanked by ammonites, hand rails that curl into ferns, bronze door manages formed like ibis skulls. As the earliest life sciences organization in the western hemisphere, the academy has actually built up a chest of exceptional specimens. Amongst the 19 million or two specimens housed here are plants obtained on the Lewis and Clark Expedition, blue marlin attracted by Ernest Hemingway, and America’s very first installed dinosaur skeleton.

Many of the academy’s most simple yet impactful treasures are submitted away on its 2nd flooring, in an office crowded with hulking cabinets and microscopic lens. Beside among these microscopic lens, manager Marina Potapova pops open a notebook-sized plastic container overflowing with glass slides. To the inexperienced eye, these average slides appear dirty– each appear like it’s been smeared by unclean fingers.

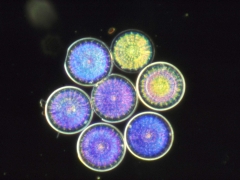

But as quickly as Potapova slips one under a microscopic lense lens, the slide’s contents impress. Lots of diatoms– tiny, single-celled algae enclosed in strong silica walls and discovered any place there is water– are repaired to the slides in a myriad of shapes.

Some are lengthened like baguettes or flattened into dishes while others hook together to look like clear centipedes. Others are barbed like harpoons or formed like chubby sea stars. Some even look like elaborate stained-glass windows. Under a microscopic lense, a couple of drops of dirty pond water end up being a kaleidoscope of diatom variety.

The appeal of diatoms is remarkable. Their eco-friendly significance is staggering. Diatoms anchor marine food webs by feeding whatever from tiny zooplankton to massive filter feeders. (Case in point: researchers have actually deduced that the increase of whales some 30 million years ago mirrors a spike in diatom variety.) Diatoms likewise have an outsized climatic effect. As one of the world’s most respected organisms, diatoms siphon damaging gases like co2 out of the air and produce huge shops of oxygen as they photosynthesize. It is approximated that approximately one-quarter of the air we breathe is developed by diatoms.

More than 4 million specimens of these important algae are plastered onto numerous countless slides and housed in the academy’s diatom herbarium. Just London’s Natural History Museum shops more slides of diatoms.

Although the academy’s diatoms no longer feed the planktonic masses or pump oxygen into the environment, they do hold hints about how the marine world is altering. As their hard shells sink to the bottom of a body of water, they are saved in the sediment for centuries. When scientists utilize a sediment core to drill down into the muddy bottom of an estuary, they are gathering diatoms transferred over the eons.

In addition to abounding and sturdy, diatoms are likewise an important barometer for a range of ecological conditions. The presence of specific diatom types can assist researchers determine whatever from commercial contamination to oxygen exhaustion. Potapova and her coworkers have actually just recently utilized these water condition time pills to evaluate how speeding up water level increase is threatening New Jersey’s seaside wetlands.

Thanks to a relative scarcity of ecological tracking, the historic decrease of these essential marshes– which hoard carbon, supply nursery premises for fish, and buffer the coast from storms– has actually mostly been obscured, making repair efforts bit more than uncertainty.

However, the countless diatoms saved at the academy are assisting the scientists track the fall of the seaside wetlands as the ocean increases, which might assist prepare for the coast’s future. “Diatoms are definitely indispensable ecological archives,” Potapova states. “You can presume the future from what they inform you about the past.”

Considering the academy’s history, it is no surprise that the storied organization has actually ended up being a center for diatoms. With the introduction of available microscopy in the 1850 s, a number of Philadelphia’s gentleman biologists were mesmerized by the world of minute microorganisms, ultimately developing the Microscopical Society of Philadelphia at the academy.

Because of their striking charm, diatoms took the microscopical society by storm. To satisfy their interest, a number of these diatomists headed east to the New Jersey shoreline to gather samples, which they installed onto glass slides utilizing a constant hand and a brush overflowing with pig eyelashes. The enthusiasts would then collect at the academy to flaunt their slides at premium luncheons.

The academy’s early members were plainly passionate about diatoms, however many were novices and released little research study on the myriad of specimens they gathered. Organizing the mountains of slides assembled by each collector into a cohesive collection showed to be rather the job for Ruth Patrick when she got to the academy in1933 The child of an amateur diatomist who got her very first microscopic lense at the age of 7, Patrick gravitated towards diatoms early in her youth and ultimately finished her PhD studying the tiny organisms. Regardless of her clinical qualifications, she was relegated to establishing microscopic lens and slides for the inexperienced enthusiasts. It took her years to even get subscription in the male-dominated academy. Her perseverance paid off, and in 1937 she ended up being manager of the nascent diatom herbarium.

Patrick’s very first objective was arranging the amalgamation of various collections into a combined and extensive source for taxonomic research study. When she was not installing and arranging slides, she was wading into close-by ponds and streams to gather brand-new specimens in the field, where she slowly got a gratitude for the environmental value of diatoms.

This crystalized throughout a 1948 exploration to Pennsylvania’s Conestoga River– a body of water greatly contaminated by sewage and commercial overflow. As her group gathered samples from throughout the creek, she acknowledged patterns in the diatom structure. Some types’ densities took off in locations polluted with sewage, while others grew in areas polluted with chemicals. Quickly, Patrick ended up being skilled at utilizing the presence of particular diatoms as a secret for detecting contamination in lakes and rivers. This supported the concept that higher diatom variety associated with much healthier freshwater environments– an insight ecologists created the Patrick Principle.

Patrick reinvented making use of diatoms to keep an eye on freshwater systems, however utilizing them in seaside wetlands dragged. The brackish blend of fresh and seawater in seaside zones such as estuaries produces environments that are vibrant and co