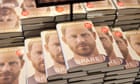

While the revelations in Prince Harry’s book have shock value, the format they come in does not. The tell-all memoir, ghostwritten with the most salacious stories parcelled into pre-publication interviews, is a media set piece. Subject, publisher and publicists all know their roles and – bar a few early leaks – things have been staged-managed effectively.

But what’s so unusual about Harry’s revelations is how they have been compared to, and intertwined with, a far less premeditated form of disclosure: therapy.

Harry’s experience in therapy has driven his outpouring – and that experience has become a stick with which the palace can beat him, as well as a strange coda to Harry and William’s advocacy for mental health awareness.

From about 2016, Prince William became perhaps the most prominent celebrity proponent of discussing men’s mental health. He launched the mental health charity Heads Together. He made a film for the BBC where he discussed mental health struggles with footballers including Thierry Henry and Gareth Southgate. He focused his campaigning efforts on men, trashing the idea of a British stiff upper lip and encouraging talk.

William’s intervention came at a time when mental health was having – this is an unpleasant phrasing – a moment in vogue. Co-opted by brands and the zeitgeist in the same way LGBTQ+ rights and feminism had been in years before, it was the issue du jour. The Headspace app exploded in popularity. Every depressing observation from the #sosadtoday Twitter account became a meme. Celebrities who had previously been scorned were suddenly celebrated for “opening up” about their depression.

every five seconds a woman doubts her abilities and that woman is me

— so sad today (@sosadtoday) December 15, 2018″,”url”:”https://twitter.com/sosadtoday/status/1074059712469946368″,”id”:”1074059712469946368″,”hasMedia”:false,”role”:”inline”,”isThirdPartyTracking”:false,”source”:”Twitter”,”elementId”:”90bbe9df-169f-4a80-b871-51ec2570d29e”}}”>

every five seconds a woman doubts her abilities and that woman is me

— so sad today (@sosadtoday) December 15, 2018

The vast majority of the attention was on middle-class people suffering from anxiety or depression. When every magazine, television programme and website launched a “special series” on mental health, they rarely talked about schizophrenia or debilitating OCD. Instead there were cloying and largely meaningless hashtags (Instagram offered #HereForYou, iHeartRadio attempted “Let’s Talk”; Burger King launched a series of depression-themed meals including the Blue Meal, Salty Meal and DGAF Meal).

And to a fault, the main solution offered was simply talking. Start the conversation, it’s time to talk, open up – these were the drumbeats of this supposed revolution.

William himself posited this as the great solution at the time: “It’s a sign of strength to talk about and look after your mind as well as your body … Catherine and I are clear that we want both George and Charlotte to grow up feeling able to talk about their emotions and feelings.”

Indeed it was William, intially, who encouraged Harry seek professional help. And there’s no doubt in Harry’s mind that this months-long revelation world tour would not have been possible without the help of his shrink. He explains in the book that seeking therapy was the beginning of a disconnect with his family. From then, his therapist becomes a crucial figure in his life. In one of the most shocking revelations, an alleged physical attack by William, Harry says immediately afterwards he called his therapist. He also told ITV: “If I wasn’t doing therapy sessions like I was and being able to process that anger and frustration, I would’ve fought back, 100%.”

Harry has recently switched from a demographic group very unlikely to seek therapy – British men over 35 – to one of the groups for whom therapy has reached almost total penetration: wealthy Angelenos. He says the US is more accepting of people seeking help. The real picture is a bit more mixed – it is true that white and wealthy Americans in urban areas are more likely to seek talk therapy than Brits, but many other Americans are prescribed drugs for mental health issues without receiving support from a counsellor or therapist. Still, it is more normalised for people without immediate mental health disorders to have regular therapy in the US – where it is a huge industry, with nine mental health startups reaching private valuations exceeding $1bn last year – than it is in the UK, where services are largely operated by an ad hoc mixture of hard-to-access NHS support and freelance psychotherapists .

Something about being a man seeking that kind of help has riled both the palace and the public.

But in the memoir, Harry claims that William believed his brother was being “brainwashed” by his therapist. This language was echoed this week by a source “close to the royal family” who told the Independent: “The King, Camilla and William believe the situation will remain unchanged while the Duke of Sussex remains effectively ‘kidnapped by a cult of psychotherapy and Meghan’.”

This is the kind of anonymous press briefing Harry suggests comes directly from his family, although we have no way of knowing if that is the case. But if it were, it would hardly be the first time a family encouraged a suffering child to go to therapy, only to be horrified when they come back with issues to raise.

Talking, is, for many people, an important step in dealing with the repression of bad things that have happened or bad things they have done. There is overwhelming evidence that talking itself alone can improve the situation – but more often it’s the starting point to other actions. Unearthing the horrors of childhood, as Harry has done in his therapy, doesn’t necessarily bring much comfort – but it can alert someone not to allow the same patterns to continue.

If we are serious about removing the stigma around mental health, it cannot be enough simply to start a conversation; we must also reckon with where that conversation goes. In Harry’s case, it has led to realisations about a cruel and sometimes abusive childhood and adult life: he was refused a hug or even eye contact from his father as he was told about his mother’s death, forced to parade publicly behind his mother’s coffin, told by his father he was a back-up and that he might not even be his real son, sent to boarding school aged eight and refused privacy at any point. In later life, he claims, his stepmother and father colluded to provide stories about his behavior to the tabloid press in order to improve their own PR standing. Is he a bit weird as an adult, at times unable to read the room, with a tendency towards defensive poshness? Absolutely. Is it any wonder why? Not at all.

Of course, just because Harry’s wellbeing might be helped by speaking to a therapist, it doesn’t follow that he needs to go on an international press tour. Where there is discomfort from the public with Harry’s disclosures, it’s not – as much of the British press would lik