Uncovering The Oil

Industry’s Dirty Secret

By Chris Foote

Every year hundreds of ships and oil rigs are sold to shipbreaking yards in south Asia where they are cut apart by low-paid migrants.

We followed a trail from the north coast of Scotland to the beaches of India to reveal how wealthy companies profit from an industry which destroys lives and damages the environment.

Every year hundreds of ships and oil rigs are sold to shipbreaking yards in south Asia.

We followed a trail from Scotland to India to reveal how wealthy companies profit from an industry which destroys lives and damages the environment.

Alang is a graveyard for ships.

Its coastline was once filled with fishing boats — but today the rusting hulks of oil tankers and ocean liners stretch for miles along the shores of this town in north west India.

The premium prices paid for steel make it a lucrative place to dismantle ships.

Alang’s high tides and sloping coastline also create the ideal natural conditions for the work.

Its shipbreaking yards are the busiest in the world and oil companies are among their biggest customers.

About a third of all vessels which are sold for scrap will end their days there.

But it comes at a cost to men like Javesh and Naveen, who work in the searing heat and pollution of the yards.

“We do not have human rights,” said Naveen.

“Sometimes we feel like we’re animals. We’re treated like insects by these people.”

Javesh and Naveen agreed to speak to Mark Daly from the BBC’s Disclosure team on condition of anonymity.

We have changed their names to protect them and their families.

Workers in the yards dismantle ships by hand with blowtorches and sledgehammers so the valuable metals they contain can be salvaged.

Little goes to waste.

Steel and wood are recycled at workshops which surround the shipyards and everything else finds its way to open-air markets in Alang where you can buy boxes of lightbulbs from oil tankers or cutlery from cruise ships.

Like most of the workforce, Javesh and Naveen are migrants from Uttar Pradesh, one of the poorest parts of India.

They live on the outskirts of the yards in shanties without running water, toilets or electricity.

“We buy scrap wood which comes out of ships and we build these places ourselves,” said Javesh.

“The company doesn’t take responsibility for the labourers at all.

“All they care about is the work.”

Shipbreaking is dangerous and dirty work and men like Javesh and Naveen are in constant danger, according to Ingvild Jenssen.

She is the founder and director of Shipbreaking Platform, an organisation which monitors the industry.

“They risk gas explosions, falling from heights, being crushed by massive steel plates that fall down — those are the main causes of the fatal accidents,” she explained.

Workers often lack basic safety gear and at least 137 lost their lives between 2009 and 2019, according to Shipbreaking Platform.

The organisation believes that number is probably only the tip of the iceberg because shipyard owners refuse to discuss accidents.

More than half of shipyard workers say they have been injured on the job, according to a survey last year by the Tata Institute in Mumbai.

During their interview, Javesh and Naveen showed our team numerous scars and burns on their legs and arms.

There is only one small clinic in Alang and more seriously injured workers have to travel to the city hospital in Bhavnagar – a 30-mile journey on unpaved roads which takes more than an hour.

Workers are also at risk from hazardous waste like asbestos and mercury contained in many of the vessels sold to the scrapyards.

“Many more workers succumb to occupational diseases and cancers years after they’ve worked at the yards because they are exposed on a daily basis to toxic fumes [and] materials at the yards,” Ms Jenssen added.

Shipbreaking is dangerous and dirty work and men like Javesh and Naveen are in constant danger, according to Ingvild Jenssen.

She is the founder and director of Shipbreaking Platform, an organisation which monitors the industry.

“They risk gas explosions, falling from heights, being crushed by massive steel plates that fall down — those are the main causes of the fatal accidents,” she explained.

Workers often lack basic safety gear and at least 137 lost their lives between 2009 and 2019, according to Shipbreaking Platform.

The organisation believes that number is probably only the tip of the iceberg because shipyard owners refuse to discuss accidents.

More than half of shipyard workers say they have been injured on the job, according to a survey last year by the Tata Institute in Mumbai.

During their interview, Javesh and Naveen showed our team numerous scars and burns on their legs and arms.

There is only one small clinic in Alang and more seriously injured workers have to travel to the city hospital in Bhavnagar – a 30-mile journey on unpaved roads which takes more than an hour.

Workers are also at risk from hazardous waste like asbestos and mercury contained in many of the vessels sold to the scrapyards.

“Many more workers succumb to occupational diseases and cancers years after they’ve worked at the yards because they are exposed on a daily basis to toxic fumes [and] materials at the yards,” Ms Jenssen added.

Wealthy companies can make millions selling ships for demolition, but Javesh and Naveen are only paid about 35p an hour.

They send whatever money they can home to their families, who they may not see for months.

“If we get scared, our families would starve,” said Naveen.

“This is what it comes down to – the labourers have to do the work… safety or no safety.”

Workers dismantle a ship in an Alang yard (Reuters, 2018)

Workers dismantle a ship in an Alang yard (Reuters, 2018)

Despite the conditions in the shipyards, workers are too afraid to speak out.

“If we say anything we are thrown out of the company,” said Javesh.

“If someone speaks they will be fired [so] no-one speaks.

“We are not treated as humans should be.

“Basically we are helpless [and] because we are helpless we keep working.”

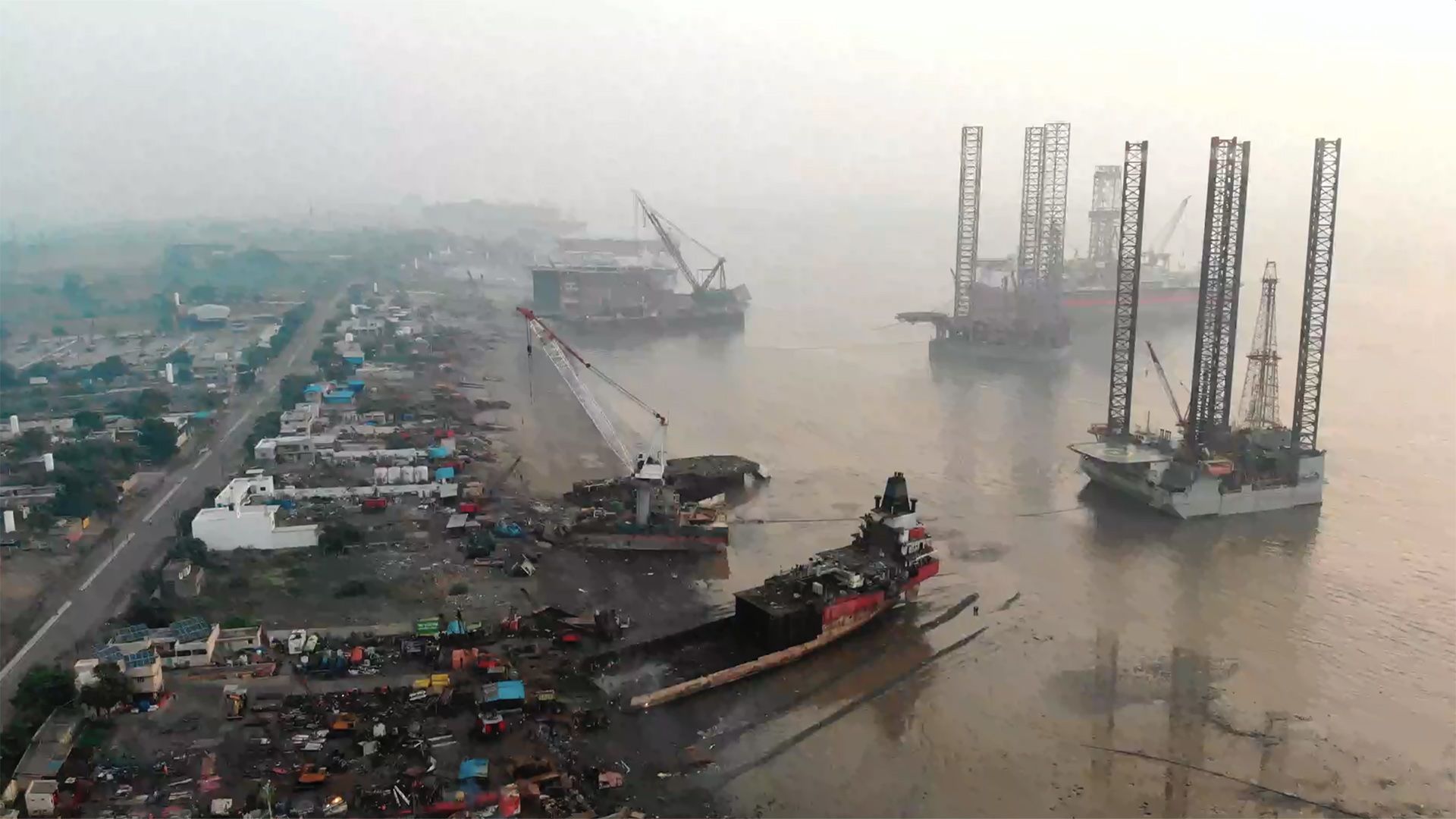

The industry has also taken a toll on the environment in Alang.

The way ships are dismantled makes it almost impossible to contain pollution.

There are no docks or harbours — instead ships are beached and sit in the open water as they are cut apart, allowing waste to wash in and out with the tide. Many yards use the “gravity method”, where chunks of metal are allowed to fall onto the beach as they are cut away.

Oil rigs are more difficult to beach so they are dumped on tidal flats up to a mile and a half away, where pieces are cut from them until they are light enough to be dragged ashore to finish the work.

It usually only takes a few weeks for a vessel to disappear, although the largest of them, like the Schiehallion — an 86,000 tonne floating factory from the North Sea which was dumped in Alang in 2017 — can take more than a year to dismantle.

Scientific studies have identified unsafe levels of poisonous heavy metals in the waters around the town, including iron, mercury, copper, zinc and lead.

Shipbreaking Platform describes the yards as “toxic hotspots”.

“When you have hundreds of vessels ramped up one beside the other… releasing toxic fumes, air pollution and heavy metals… into the sea, that pollutes the sea, the soil, and also the groundwater,” said Ms Jenssen.

“So the environmental impact… is massive.”

Fishing was once the most important business in Alang, but nets have grown empty since shipbreaking took over in the 1980s.

“In the last 20 years the size of the catch has gone down,” said Dinesh Gulab Bivagar, a community leader from Ghogha, a small town a few miles north of the shipyards.

“Before, our fisherman brought back full boats of fish.

“Now they don’t bring back as much, there aren’t as many fish in the sea.”

He estimates the catch in Ghogha has fallen by 75% in the last two decades but he is wary of blaming shipbreaking.

Few local people are prepared to be critical of an industry which is so vital to the economy in Alang.

The fish that are left may not even be safe to eat — one study from 2010 found they contained dangerously high concentrations of poisonous metals.

And new tests show the impact of shipbreaking is not limited to the marine environment.

Sediment samples collected by the BBC from one stretch of the breaking beach in Alang were analysed by experts at the Scottish Environmental Protection Agency (Sepa).

They found the sediment was more than 50% metal – which they demonstrated by placing a magnet over one of the samples.

Sammi Mallin, a scientist at Sepa, believes this is a result of the shipbreaking process.

“When we looked at the metal content of the sample under high magnification, we were able to pick out little metal spheres,” she explained.

“They’re produced when something like a high-temperature acetylene torch is used for cutting steel and they fuse to the gravel they land on.

“We would not expect to find these in a natural environment.”

The industry has also taken a toll on the environment in Alang.

The way ships are dismantled makes it almost impossible to contain pollution.

There are no docks or harbours — instead ships are beached and sit in the open water as they are cut apart, allowing waste to wash in and out with the tide. Many yards use the “gravity method”, where chunks of metal are allowed to fall onto the beach as they are cut away.

Oil rigs are more difficult to beach so they are dumped on tidal flats up to a mile and a half away, where pieces are cut from them until they are light enough to be dragged ashore to finish the work.

Workers tie a rope to a decommissioned rig at an Alang shipyard (Reuters, 2018)

Workers tie a rope to a decommissioned rig at an Alang shipyard (Reuters, 2018)

It usually only takes a few weeks for a vessel to disappear, although the largest of them, like the Schiehallion — an 86,000 tonne floating factory from the North Sea which was dumped in Alang in 2017 — can take more than a year to dismantle.

Scientific studies have identified unsafe levels of poisonous heavy metals in the waters around the town, including iron, mercury, copper, zinc and lead.

Shipbreaking Platform describes the yards as “toxic hotspots”.

“When you have hundreds of vessels ramped up one beside the other… releasing toxic fumes, air pollution and heavy metals… into the sea, that pollutes the sea, the soil, and also the ground water,” said Ms Jenssen.

“So the environmental impact… is massive.”

Fishing was once the most important business in Alang, but nets have grown empty since shipbreaking took over in the 1980s.

“In the last 20 years the size of the catch has gone down,” said Dinesh Gulab Bivagar, a community leader from Ghogha, a small town a few miles north of the shipyards.

“Before, our fisherman brought back full boats of fish.

“Now they don’t bring back as much, there aren’t as many fish in the sea.”

He estimates the catch in Ghogha has fallen by 75% in the last two decades but he is wary of blaming shipbreaking.

Few local people are prepared to be critical of an industry which is so vital to the economy in Alang.

The fish that are left may not even be safe to eat — one study from 2010 found they contained dangerously high concentrations of poisonous metals.

And new tests show the impact of shipbreaking is not limited to the marine environment.

Sediment samples collected by the BBC from one stretch of the breaking beach in Alang were analysed by experts at the Scottish Environmental Protection Agency (Sepa).

They found the sediment was more than 50% metal – which they demonstrated by placing a magnet over one of the samples.

Sammi Mallin, a scientist at Sepa, believes this is a result of the shipbreaking process.

“When we looked at the metal content of the sample under high magnification, we were able to pick out little metal spheres,” she explained.

“They’re produced when something like a high-temperature acetylene torch is used for cutting steel and they fuse to the gravel they land on.

“We would not expect to find these in a natural environment.”

Alang has a global reputation as a centre for shipbreaking, but it is illegal for companies in the UK, the United States and Europe to send ships there without removing hazardous waste from them first — a costly and time-consuming process.

“Developing countries should not be the dumping ground of hazardous materials from the developed world,” says Ingvild Jenssen, from Shipbreaking Platform.

“A vessel containing asbestos and other toxic materials should not be exported to India or Bangladesh or Pakistan for breaking, but recycled in a facility that can handle and properly dispose of these hazardous materials.”

So how did 200 vessels – many formerly owned by European companies – end up in Alang last year?

Oliver Holland is a lawyer at Leigh Day, a law firm which specialises in human rights cases.

He says the answer is companies known as cash buyers who act as middle-men between ship owners and shipbreakers.

“The cash buyer is simply an intermediary, and is there, we