If you just came back from an overseas trip with a fever and a cough, you’ll be prioritized for a COVID-19 test in Manitoba and Nova Scotia, but not Alberta or Quebec. And some provinces are expanding who can get tests, as others narrow them. Why? And what does it mean for the accuracy of Canada’s case numbers?

If you just came back from an overseas trip with a fever and a cough, you’ll be prioritized for a COVID-19 test in Manitoba and Nova Scotia, but not B.C., Alberta or Quebec.

Some provinces are expanding the groups of people who can get tests as others narrow them — and that may change from day to day. Why? And what does it mean for the accuracy of numbers of infections in different provinces and territories?

Here’s a closer look.

How variable is testing across Canada?

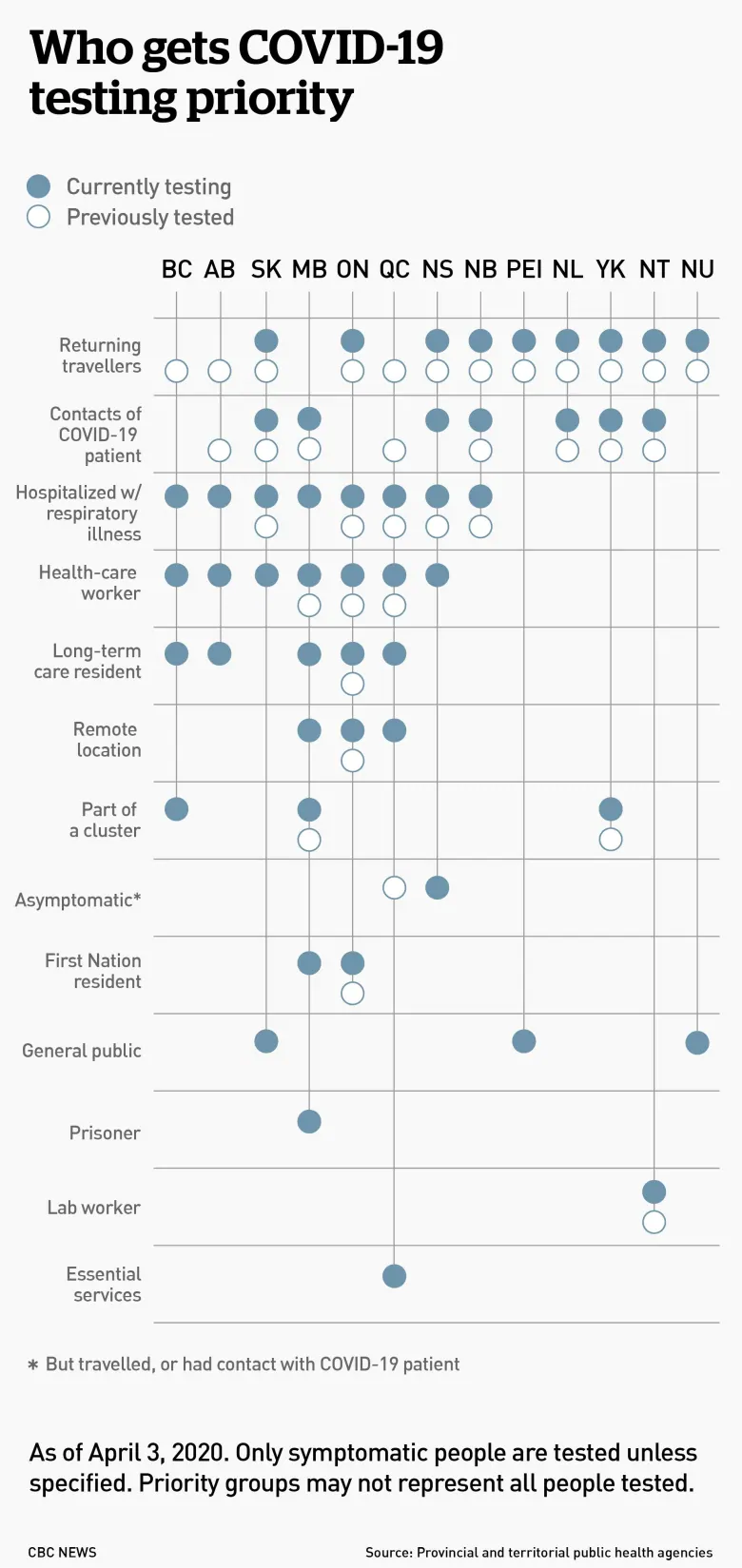

Each province or territory has a different rate of testing and different groups that are targeted, sometimes unique to that region. For example, the Northwest Territories lists people who have had lab exposure to biological material, while Manitoba and Ontario prioritize people in remote areas or work camps.

Many don’t test people outside those targeted groups, even if they have symptoms, and most even require people within those groups — such those who’ve been in contact with someone who has tested positive — to have symptoms before they can be tested.

To make things even more confusing, the priority groups change from day to day: Alberta, Manitoba and P.E.I. have all announced changes to their testing criteria in the past two weeks, and Quebec has announced multiple changes in that time.

Why are only certain groups prioritized for testing?

There is generally a shortage of tests, materials needed to run the tests and lab workers to run them. Exactly what is in short supply — and how short those supplies run — varies from province to province and possibly from week to week. That’s why some provinces, such as New Brunswick, are running relatively few tests, and some, such as Ontario, have long backlogs.

But to some extent, the shortage is Canada-wide — and worldwide.

“You’re just not going to be able to test everybody,” said Greta Bauer, a professor of epidemiology at Western University.

That means tests need to be rationed and each province or territory decides exactly which groups get priority, based on two main goals:

-

Providing appropriate care to those who need it.

-

Improving the government’s response to the pandemic.

As a result, patients who need treatment in hospital are usually prioritized. Those who don’t need medical treatment, such as those with mild symptoms, often aren’t tested at all — they’re just told to self-isolate at home.

“We’re going to save the tests for the people who are really sick,” said Gaston De Serres, an epidemiologist practitioner at the Institut national de santé publique du Québec and a professor at Laval University, in an interview in French.

And to make sure those people can be properly treated, he said, health-care workers must also have good access to testing to ensure they can continue to safely work with patients.

Many people may think testing — and the daily infection numbers that come from the results — are an important way to measure the spread of COVID-19 in their communities. And more widespread testing would presumably better do that.

But while that is a way that governments might use testing, right now it “is not the primary use of tests,” said Bauer.

Why are priority groups changing so much?

Bauer acknowledged testing criteria are changing quickly — something that she called “appropriate” as the pandemic moves through different stages, particularly since a main goal of testing is to improve government response.

“That is, I think, what’s driving most of the changes we’ve seen,” she said.

Testing also needs to be responsive to what’s happening in di