In late February, the virus specialist Nevan Krogan called a morning meeting at his UCSF laboratory in Mission Bay and informed 20 fellow scientists that their lives will change.

The brand-new coronavirus, which emerged in China, was now spreading out from person to person in California.

” I just sort of turned out,” remembered Krogan, 44, a tall, energetic Canadian native. “We need to do this now. And they resemble: ‘Yeah.'”

Two months later, the results of that mission remain in, and they’re likely to draw broad attention, thanks to a striking paper that Krogan and his associates released Thursday in the journal Nature.

” We have actually discovered something about this infection that I hope can help individuals,” he stated.

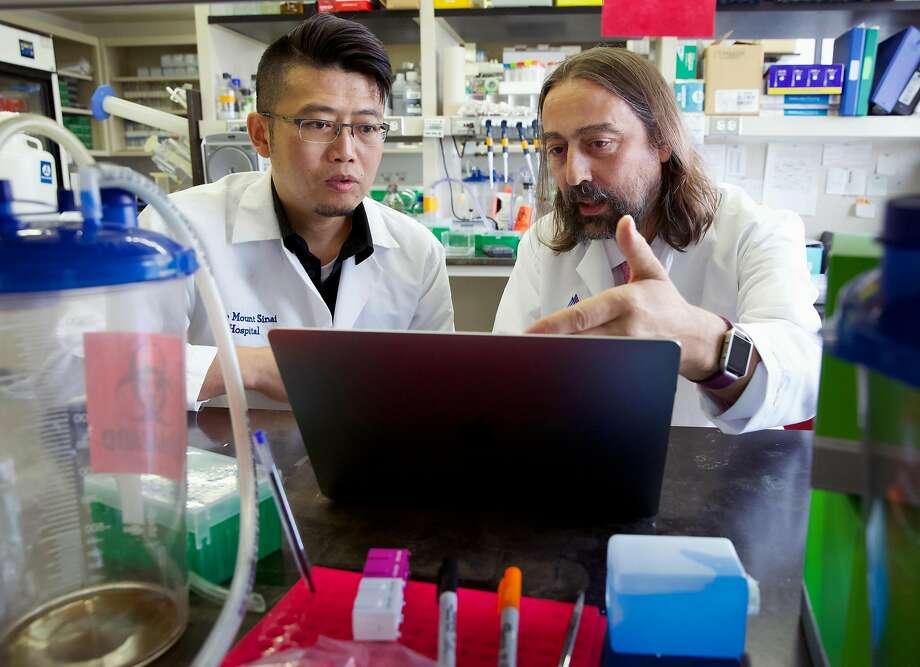

Inside the Krogan Laboratory led by Dr. Nevan Krogan, director of Quantitative Biosciences Institute and teacher of cellular molecular pharmacology at UCSF.

( Stephen Lam/ Special To The Chronicle

None of the five FDA-approved drugs is authorized to treat COVID-19, and some have unsafe side results.

One is hydroxychloroquine, a malaria treatment made well-known by President Trump, who has hawked it as a COVID-19 treatment versus the advice of health experts. Hydroxychloroquine can be hazardous to the heart, and a current research study of coronavirus patients at Veterans Health Administration medical centers found a greater death rate in clients who got the drug.

The other four authorized drugs that stopped the virus in the lab tests were haloperidol, typically sold as Haldol, a commonly offered drug to deal with schizophrenia; cloperastine, a cough suppressant that has actually been around considering that the 1970 s; clemastine, an antihistamine; and progesterone, a natural hormone that is likewise offered as a medication.

The remainder of the drug candidates flagged in the Nature paper are experimental substances. Formerly, many have been studied as possible weapons versus cancer.

The paper is more than a list of drugs.

He even believes they might repeat the process all over once again, effectively, when the next pandemic hits. “In a few years,” he stated, “we might be dealing with Covid-24”

San Francisco Chronicle)

The starting gun

Krogan very first become aware of the epidemic in China late last year. At the time, SARS-CoV-2 was just another emerging virus, worth keeping an eye on, and for him, intrinsically interesting.

The white walls of his workplace at QBI, within the School of Pharmacy and housed in a modern-day biotech building on UCSF’s Mission Bay school, are covered with dry-erase notes on past tasks about dengue fever, the Zika infection, Ebola, HIV. “That’s the game plan to cure HIV,” he said on a current early morning, pointing to a cluster of scribbles. “It’s all associated.”

He wore a surgical mask, denims, a Canadian Maple Leaf pin and a brilliant purple sports jacket produced him by a Ugandan tailor named Muwanguzi Charles; they satisfied years ago when Krogan was doing infectious-disease research study there. (Reached through Facebook Messenger, Charles said of Krogan, “He likes vibrant colors.”) Taking a few vigorous steps down the hall, he offered a tour of the Krogan Lab itself, which included the typical clutter of molecular biology: Flasks, shakers, micro-pipettes for managing fluids, honeycombed plastic plates, incubators for growing cells, science jokes taped to the walls:

KEEP CALM AND PIPETTE ON

CARE

COMBINED GENDER LAB

NO FALLING IN LOVE OR CRYING PERMITTED

Krogan, who is also an investigator with the Gladstone Institutes, grew up in Regina, Saskatchewan, a city in northwestern Canada better understood for producing hockey players than researchers.

After joining UCSF in 2006, Krogan started to tackle infections, and over the next 13 years, his lab established an uncommon capability that would, in the middle of a worldwide pandemic, prove really convenient.

Dr. Nevan Krogan, UCSF teacher of cellular molecular pharmacology who leads a worldwide group of scientists studying how to fight the coronavirus, at his Krogan Laboratory in San Francisco. San Francisco Chronicle)

An infection can’t exist by itself; it needs our proteins to reproduce, to overturn the body.

Eventually, he thought, those maps could lead to effective brand-new antiviral drugs. The infection can’t change the host cells, though, which suggests that drugs focusing on the host can stay effective for longer and can possibly work against numerous types of viruses.

Krogan’s laboratory created maps for Ebola, Zika and HIV, amongst other infections.

On Jan. 24, when there were only 2 verified coronavirus cases in the U.S., Krogan spoke about a brand-new task with 2 close coworkers in his laboratory, David Gordon and Gwendolyn Jang. They were all curious about SARS-CoV-2, and it was natural to start looking at it.

On a website called GenBank, scientists in Washington had shared the hereditary code of a SARS-Co-V-2 stress found in a patient there. Gordon and Jang started to analyze the infection’ gene sequence.

Using cloning methods, they developed copies of the genes, one by one. They fashioned each piece of the infection into a kind of hook, reducing the hooks into human cells to see which human proteins got stuck to them. Those were probably the proteins that the virus needed most– and the ones most pertinent to disease.

In the middle of this early research, Krogan flew to New York City the very first week of February, and went to a longtime pal, Adolfo Garcia-Sastre, director of the Global Health and Emerging Pathogens Institute at Mt. Sinai.

A bearded, 55- year-old Spaniard, Garcia-Sastre is one of the world’s leading specialists in influenza viruses and vaccines.

” I was informing him, this thing is going to go all around the world,” Garcia-Sastre recalled.

Financial collapse.

” He simply said it sort of matter-of-fact,” Krogan recalled. “‘ Do you desire some more wine?'”

When Krogan responded with a joke, saying maybe they should go hide up in Canada, Garcia-Sastre was having none of it. This was a time “for us to do some science,” he stated.

Virologist Adolfo Garcia-Sastre (best), director of the Global Health and Emerging Pathogen