Pandemics are inexorable– and the canon of plague literature is a chronicle of nature’s senselessness and its indomitability. “There was no apparent cause,” composed Thucydides in 431 BC, about the Plague of Athens, an epidemic of typhus, likely, that laid the city to waste. “Strong and weak constitutions showed equally incapable of resistance, all alike being swept away.”

Boccaccio also begins The Decameron, his masterful collection of tales (c. 1353) told by young adults fleeing Florence for the countryside, with the shock of pester– and subsequent plot twists, whether slapstick or tragic, unfold as if ordained. Anything goes. “Due to the fact that of the turmoil of today age, the judges have deserted the courts, the laws of God and male remain in abeyance, and everybody is given ample license to maintain his life as finest he might,” says Dioneo on Day 6. Previously, on Day 3, Dioneo introduces into happy smut, in which a penis is a devil and a vaginal area is hell. And on Day 4, Lisabetta buries her fan’s head in a pot of basil. In context, that makes ideal sense.

May2020 Subscribe to WIRED

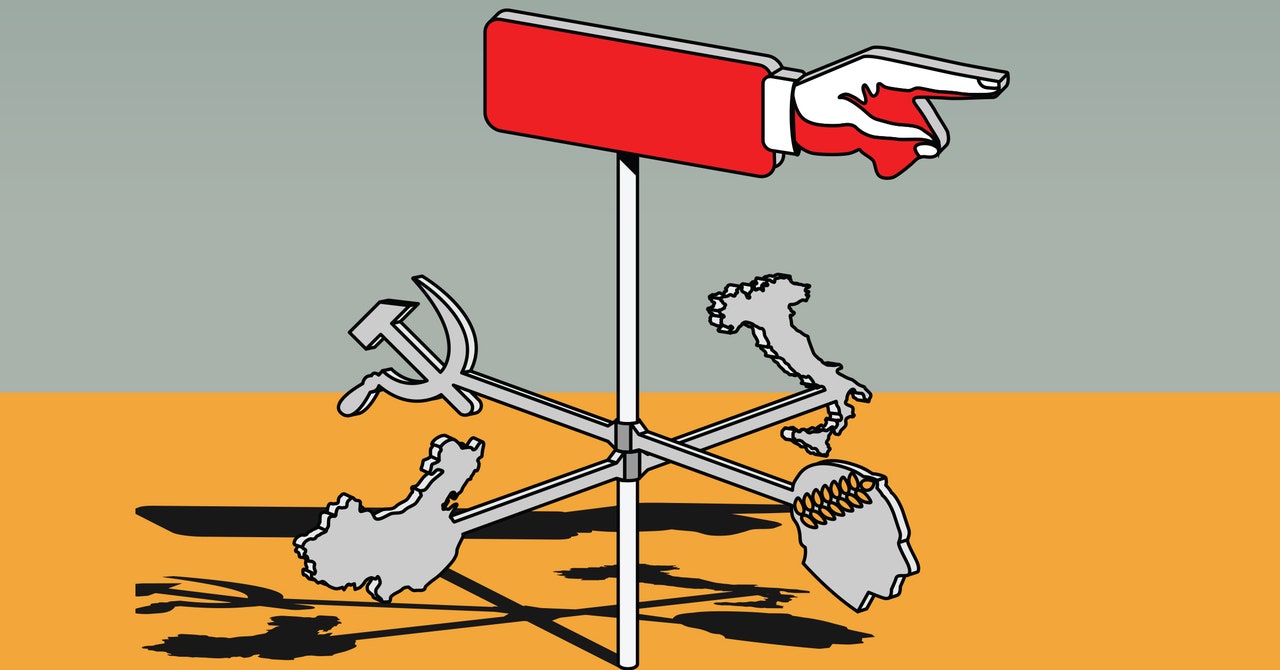

Illustration: Zohar LazarBut even as plague years create twisty brand-new fables, each time a novel pathogen gets on a worldwide tear, existing human stories are shattered.

Thus, the literature of plagues faces inevitability along with reeling what-ifs. Plagues don’t come f