Image copyright

Image copyright

Getty Images

Can rescue spending clean up the global economy?

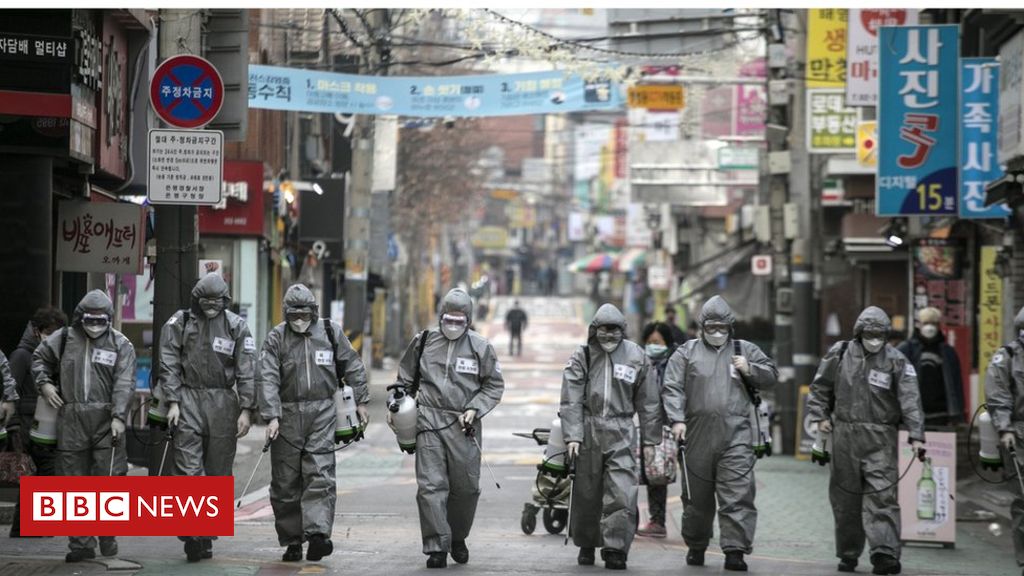

Coronavirus shutdowns around the world have pushed countries into crisis-mode, prompting a massive rescue spending in an effort to soften the blow from what is expected to be the worst economic contraction since the 1930s.

As of 7 April, countries around the world had approved more than $4.5tn worth of emergency measures, according to the IMF. That figure has only grown in the weeks since.

So how do the responses compare?

New spending

Columbia economics professor Ceyhun Elgin has been working with colleagues around the world to track the responses in 166 countries.

By his calculations, Japan’s response has been among the most aggressive, with a spending package estimated at roughly 20% of the country’s economy. (It is topped only by Malta, which benefits from European Union funds.)

That compares to rescue spending estimated at roughly 14% of GDP in the US, 11% in Australia, 8.4% in Canada, 5% in the UK, 1.5% in Colombia and 0.6% in Gambia.

But that ranking looks different if measures beyond spending, such as central bank actions, are considered.

In the biggest European countries, for example, government pledges to guarantee new loans provided to businesses hurt by the shutdowns – a move meant to keep banks lending and stave off bankruptcies – has accounted for a major part of the response.

America’s central bank has also stepped in with lending programmes with a similar aim.

Factoring in those kinds of actions puts France at the top of the pack and moves the UK into fifth place, instead of 47th.

Prof Elgin says the biggest responses have occurred in countries that are richer, older – and have fewer hospital beds. Countries like the US and Japan are also in a better position to finance new spending, since investor willingness to buy their bonds means they benefit from low borrowing costs.

However Prof Elgin says size shouldn’t be mistaken for effectiveness, noting that countries are deploying funds differently.

“All the different contents in these packages, they might have different multiplier effects, creating different outcomes,” he says.

Relief directed at companies tends to be a phenomenon of “advanced economies”, says Paolo Mauro, deputy director of the IMF’s fiscal affairs department. While the sums involved are potentially significant, he says such programmes tend to be rel