Image

Long-familiar viruses, even ones that are every bit as contagious, can’t do that, because of a phenomenon called herd immunity.

It works like this: The more people there are in a community who have protective antibodies, either through vaccination or past exposure, the less likely an infected patient is to encounter someone who lacks them and pass the virus along. Above a certain threshold, the virus can’t spread readily enough for an outbreak to grow.

That’s why diseases like measles and chickenpox have become rare in the United States even though not everyone gets vaccinated: Enough people do to achieve herd immunity.

Scientists and policymakers hope we’ll get to that point with the coronavirus, too. But a crop of new studies suggests that herd immunity is still very far away.

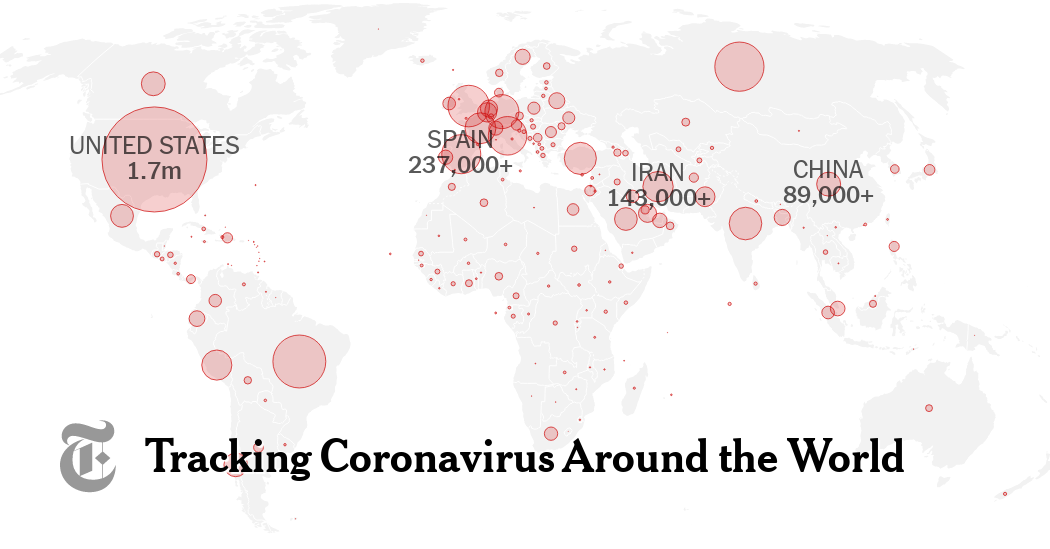

Epidemiologists don’t know yet exactly where the threshold is for the coronavirus, but they expect to find it somewhere between 60 and 80 percent of the population. Even New York City, the center of America’s worst outbreak, is still far below that: Only around 20 percent of residents tested in a survey in early May showed any antibodies, and that may be an overestimate.

Some countries — notably Sweden, and briefly Britain — experimented with minimal social distancing restrictions in an effort to develop immunity in their populations. But no more than 7 to 17 percent of people there seem to have antibodies so far.

“We don’t have a good way to safely build it up, to be honest, not in the short term,” said Michael Mina, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “Unless we’re going to let the virus run rampant again — but I think society has decided that is not an approach available to us.”

Unproven premise: The hopes for herd immunity — and for a vaccine — rest on the belief that the antibodies will protect against reinfection. There is some evidence suggesting that people do achieve immunity to the coronavirus, as they do with many other viruses. But it is not yet certain whether that’s true in all cases, or how robust the immunity may be, or how long it will last.

How big a risk do surfaces pose?

Groceries, packages, elevator buttons, doorknobs. Many people worry about touching all kinds of surfaces that others may have handled, for fear of infection. Should they?

To catch the virus that way, a series of things has to happen in just the right way. Droplets from an infected person’s sneeze or cough would have to get onto the surface; then you would have to touch it while enough virus particles remained viable; and then you would have to touch your eyes, nose or mouth.

Our Well editor Tara Parker-Pope explains that timing and quantity are important. The virus is fragile and begins to disintegrate within hours; though some particles can last up to three days on plastic or steel, there may not be enough left by then to infect you.

And you can break the chain of contamination completely with the pandemic’s golden rules: Wash your hands often, and avoid touching your face.

The New Yorkers still getting sick

After two months of stay-at-home restrictions, New York City has flattened its curve — but many people are still becoming infected. More than 13,000 people in the city tested positive for the virus in the last two weeks.

Our colleague Andy Newman told us that after seeing mask-wearing in the city “go from being a weird outlier thing to the near-universal conduct,” he wondered: “How is it that people are still managing to get sick?”

Epidemiologists, doctors, health officials and patients told him that the people catching the virus now in the New York area include essential workers and their families; elderly people; people who cannot socially distance at home; poor residents of the Bronx; and farm workers who live outside the city.