Two areas of the brain play critical roles in the experience of stress and the repair of calm, an imaging research study has found.

The impacts of stress on the mind and body, such as heightened awareness and a fast heart beat, are a mixed true blessing for modern human beings.

In our distant evolutionary past, the stress of coming across a starving predator or squaring up to a competing helped to keep us alive.

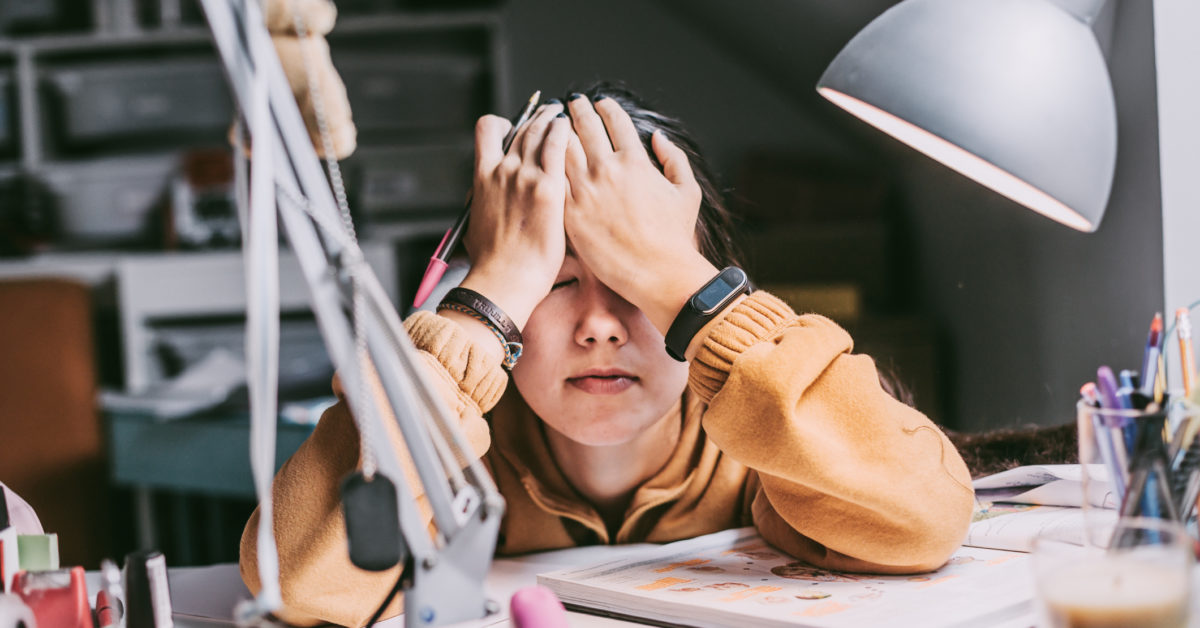

In the contemporary world, however, the instant mental and physiological impacts of stress in circumstances, such as an examination, a task interview, or a first date, can be counterproductive.

More seriously, persistent tension has associations with even worse physical and psychological health

Thankfully, unlike other animals, human beings can establish cognitive methods for reducing their subjective experiences of tension.

Effective coping strategies that psychologists have actually determined include expressing stress-related feelings, either verbally or in writing, reappraising a demanding circumstance to see it in a more favorable light, and conscious attention

By studying animals, biologists have learned a good deal about how the central nervous system manages the physiological effects of tension.

However investigating how the brain manages the subjective experience of difficult occasions has actually shown more tough.

” We can’t ask rats how they are feeling,” says Elizabeth Goldfarb, Ph.D., associate research scientist at the Yale Tension Center, part of Yale School of Medication in New Sanctuary, CT.

To find out more about the neural correlates of feeling worried, Goldfarb and her coworkers utilized functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to scan the brains of 60 volunteers as they took a look at sets of stress-inducing and neutral or peaceful pictures.

The report appears in the journal Nature Communications

The researchers revealed the participants stress-inducing images, such as a snarling pet dog, mutilated faces, and filthy toilets. On the other hand, the neutral or peaceful images included individuals reading in a park and scenes from nature.

After viewing each set of images, the researchers asked the participants to push buttons to rate how stressed they felt on a scale of 1 to 9 (1 for not worried at all, 9 for very stressed). The volunteers also ranked how calm or unwinded they felt.

The scientists were interested to see how the connectivity