In 2020, Black women hold four of the world’s biggest beauty pageant titles. But first, in 1949, there was Beryl Dickinson-Dash — the Montreal-born daughter of a railway porter who became queen of winter carnival at one of Canada’s most elite university campuses.

Listen to the full episode29:35

She was never supposed to be in McGill University’s 1949 Carnival Queen competition in the first place.

A third-year arts student, Beryl Rapier — then Beryl Dickinson-Dash — hadn’t considered entering the annual contest. She never thought of herself as exceptionally beautiful, and beauty contests just weren’t her thing.

And not insignificantly, Rapier is Black. At her majority white university, she didn’t even know if she was eligible to be elected queen of its winter carnival, a celebration that originally raised publicity for the school’s winter sports.

Today, Black women wear the crowns for four of the world’s biggest beauty pageants: Miss USA, Miss Teen USA, Miss Universe and Miss World. Up until late last year, that list included Miss America as well.

But the pageant world has historically been a white space, and Black women participating — let alone winning — have been few and far between. The first African American Miss America wasn’t until 1984, when actor Vanessa Williams won.

It’s a similar story here in Canada. Carleton University’s Patrizia Gentile knows the long history of Canadian beauty pageants well. She’s writing a book titled Queen of the Maple Leaf: Beauty Contests and Settler Femininity that will be out in the fall.

In the post-war period, beauty contests were ubiquitous.

“These beauty contests are about the white nation. They’re about exemplifying the values of Canada as a white heterosexual state,” said Gentile, an associate professor with Carleton’s Institute for Interdisciplinary Studies.

The fact Rapier won at McGill is particularly notable. The school was a “bastion of white elitism” that would have had restrictions, formal or informal, around race and religion, she said.

“The fact that Beryl actually won … is quite extraordinary, as a feat,” Gentile said.

Nominated without knowing

And yet, 71 years ago, Rapier, the Montreal-born daughter of a railway porter, became queen of one of Canada’s most elite post-secondary campuses.

“My soon-to-be husband’s roommate … saw I had given my husband a picture for his birthday and his roommate posted the picture, unknown to him and unknown to me,” said Rapier, from an NPR-affiliate studio where she lives in Las Vegas. “I was coming up to class one day, and I thought ‘Gee, why is my picture here?'”

Leighton Hutson had put Rapier forward to be the Carnival Queen, and obtained the 25 signatures required from male students to nominate her. In total, 26 young women received enough signatures to move to the next phase: a ceremonial tea during which the women would be interviewed by radio stations and judged on their ambitions, versatility and personality.

“They cut us down to about 15,” Rapier said. “They interviewed us again, and had us walk and talk and do that kind of stuff.”

The final five

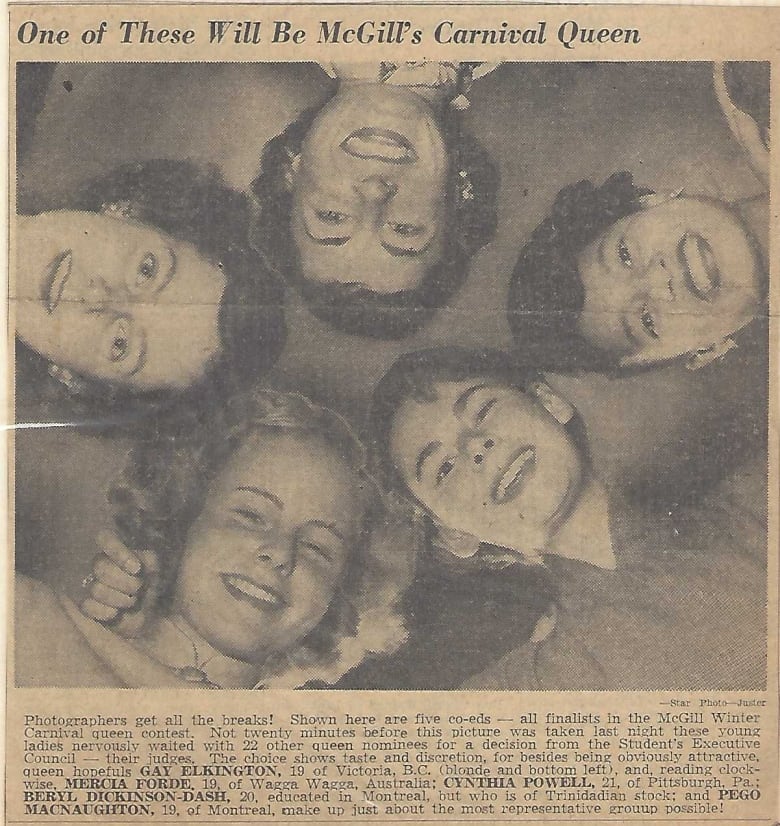

Rapier was shocked when she then became one of the five finalists — four of whom would eventually be princesses, or ladies in waiting, and one who would wind up queen.