Published September 1, 2022

15 min read

New Freedom, PennsylvaniaThe hour struck three and the little shop of clocks erupted in sound, a chaotic chorus of chimes. No two sounded the same. There were tall grandfather clocks and tiny cuckoo clocks, dome-shaped anniversary clocks and caseless skeleton clocks. There was a small, battery-powered kitchen clock on the wall above the register, to tell the time. It was the only one that did not seem to make a sound.

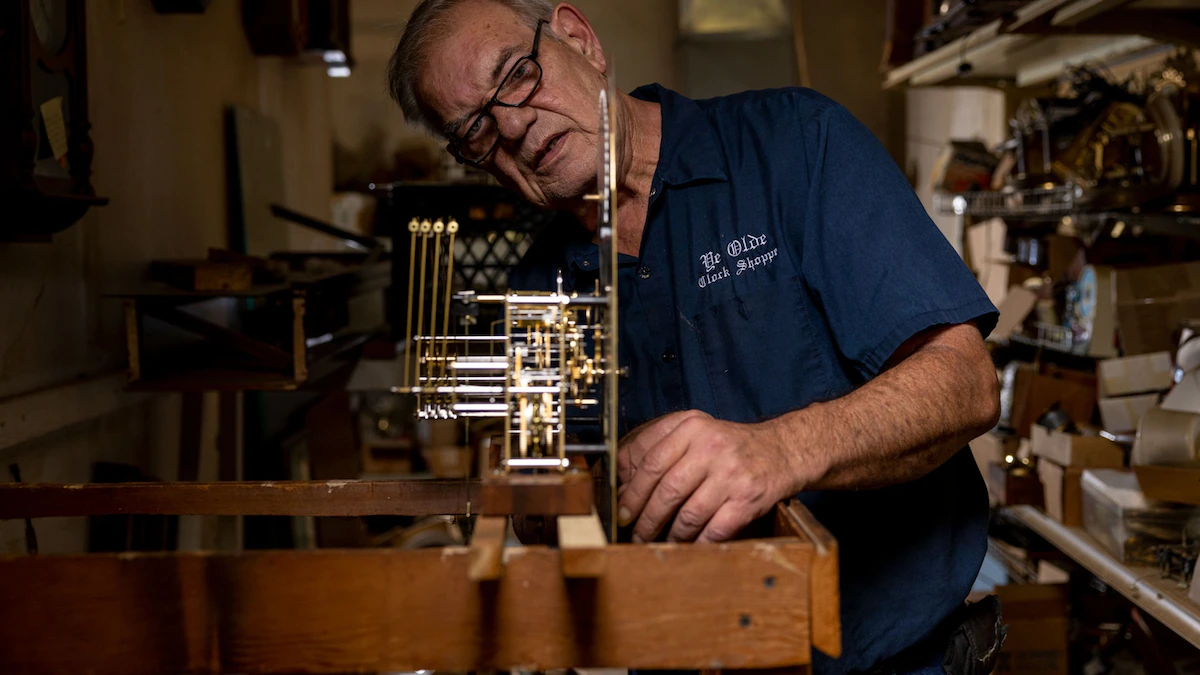

Standing in the middle of it all was Theron “Jeff” Jeffery, a tall, gruff man with thick fingers and slick white hair. He has been fixing clocks for a living for more than 40 years. For 30 of those he’s been here, in his Ye Olde Clock Shoppe, along the side of a road in the rural town of New Freedom, Pennsylvania.

“You have to have several ingredients in one body to be a clockmaker,” Jeffery says, bent over his workbench, his eyes fixed on a verge escapement—a thin rod that clicks into a rotating crown-shaped wheel, at evenly-spaced intervals, to ensure that a clock ticks at a regular pace. This one needed replacing. “You have to have very good eyesight, to see what you’re doing. You have to have very good manual dexterity to work with the small parts. You have to have a very good understanding of—or at least an ability to understand—physics.”

Jeffery himself comes from a family of skilled tradesmen. One of his grandfathers was a master blacksmith; the other was a carpenter. His father was a military engineer with a background in physics. “It’s not a coincidence,” Jeffery says. “Here I am.”

In his more than four decades on the job, Jeffery has repaired thousands of clocks—from the common (grandfather clocks, cuckoo clocks) to the complex or strange (ships’ clocks, urn clocks). His work is largely analog, relying on gears, weights, and moving metal pieces. In boxes of old clock parts delivered to him by people cleaning out their homes, he has found relics of bygone eras: the original Slinky, a clay pipe, a handful of bullets from the Civil War.

His work forms part of an occasional National Geographic series featuring individuals who have become “Masters of their Craft:” A Pennsylvania clockmaker, a Colombian filigree jeweler, a sailor trained in the ancient tradition of Polynesian wayfinding. Wherever they may be, with or without public recognition, they are not only focused, learned experts, but often also repositories of culture and history, with insights into how we live.

Jeffery is a horologist: someone whose work deals with the measurement of time. His workspace sits at the entrance to a labyrinth of dusty backrooms stuffed with tools and machines and cabinets. On this afternoon in late June, there were curved glass covers, dial faces marked with roman numerals, and tall gold-colored pendulums. Jeffery opened and closed dozens of little drawers, showing springs, nuts, and screws—as well as hour- and minute-hands, thumb-sized wooden cuckoo birds, and metal gears of all kinds.

It is striking that most of a clockmaker’s work is spent focused on parts so small, in the service of something so big as keeping time. For a mechanical clock to function with any kind of accuracy, all of these tiny parts must work together in perfect synchronicity. And the ubiquity of these precision timekeeping devices has fundamentally revolutionized the way we work and live.

“Just look around your house,” Jeffery says. Most of us have a clock on the stove, a clock on the microwave, a clock on the coffee maker. We keep clocks in our bedrooms, clocks on our wrists, clocks in our pockets. “Imagine a world where the average household only had one.”

Or none.

History of telling time

Until relatively recently, time in the non-clock world was delineated not by hours and minutes but by natural events. When people were hungry, they ate; when people were tired, they slept. Especially in rural areas, animals—like the crowing rooster or the croaking frog—helped move those processes along, as did the sun and the stars, when the skies were clear. Some early clocks also reflected these natural rhythms: sundials in Ancient Rome and Greece, for example, and water clocks in East Asia. But they were far from precise.

The ancient Egyptians were among the first to divide each day into 12 segments for daylight and 12 segments for dark. This meant that the “hours” lengthened or shortened with the seasons. In European cities—especially in colder, northern climates where the winter sun only shines for a few (often-cloudy) hours per day—more creative rules sometimes had to be established. In 14th century Paris, for instance, a tanner’s workday began when it was light enough to recognize a familiar face in the street, and ended once it was too dark to tell two similar-looking coins apart by sight.

Though Europe was far behind China and the Islamic world in terms of science and technological innovation during the Middle Ages, it is hardly surprising that the first mechanical clocks were invented there in the 14th century, writes David Landes in his landmark book on timekeeping, Revolution in Time. One big reason for the division of the day into equal, set hours was religion, Landes says. For Western practices of Christianity, prayer occurred in groups and at fixed times—time stamps that would come to be known as the “canonical hours”—marked by the ringing of monastic bells.

In Europe, the monastic bells increasingly regulated ever