This article was originally featured on Task & Purpose.

From car keys to glasses to rifles, everyone misplaces something important from time to time. But when you’re the U.S. government, sometimes that important thing is a superweapon that is designed to destroy cities and kill millions of people.

Over the decades, the U.S. military has had 32 nuclear accidents, also called “Broken Arrow” incidents. These incidents include accidental launches, radioactive contamination, loss of a nuclear weapon or other unexpected events involving nuclear weapons. Luckily, of those 32 accidents, there were only six U.S. nuclear weapons that could not be located or recovered, and of those six weapons, only one was capable of a nuclear detonation when it was lost.

While even one missing nuclear weapon sounds scary, it’s worth noting that the Soviet Union lost far more during the Cold War, often due to submarines sinking with a dozen or more nuclear missiles on board.

“Compared to the Soviet Union, the U.S. record is pretty impressive, given how many nuclear weapons it has operated and transported everywhere over the years,” Hans Kristensen, director of the Nuclear Information Project for the Federation of American Scientists, told Task & Purpose.

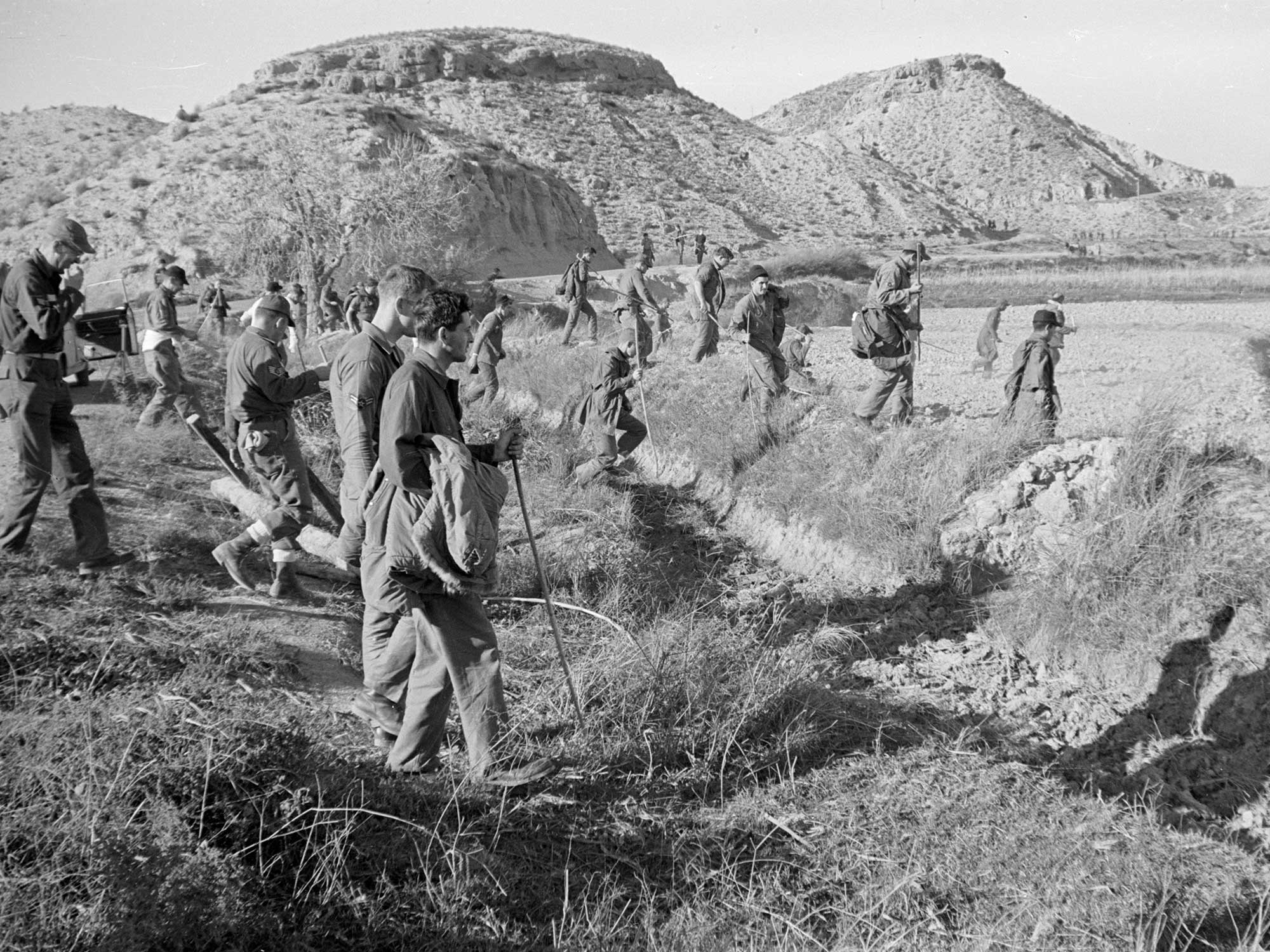

In fact, U.S. government agencies often go to great lengths to secure lost weapons. One such incident occurred on Jan. 17, 1966, when a B-52 and a KC-135 refueling tanker collided over southern Spain and scattered four B-28 thermonuclear bombs around the fishing village of Palomares. The conventional explosives for two of the bombs exploded, but the nuclear components did not detonate because they were not armed. The U.S. military sent troops to pick up the undetonated one that fell on land, clean up the radioactive pieces scattered by the two which detonated, and find the fourth which landed in the sea. The U.S. government even dispatched a submarine to find the one in the Mediterranean Sea. Called ‘Alvin,’ the small deep-ocean sub was high-tech for its time, but the crew nearly died when the sub was almost entangled in the parachute that was still attached to the bomb on the ocean floor. Meanwhile, the service members who helped find the landward bombs and clean up the wreckage also developed cancers which they say are linked to that mission 56 years ago.

Considering the extent to which the U.S. looks for lost nukes like it did in Palomares, the stories behind the five instances where recovery crews could not locate or recover weapons are extraordinary. Below is a list of those five accidents, one of which resulted in two missing nuclear weapons. Keep in mind that in all but one, the lost nuclear weapons did not include the pit or capsule that contains the components for triggering a nuclear detonation. That means we can all sleep a little easier knowing those weapons cannot blow up a city. However, the U.S. government still classifies those pit-less devices as nuclear weapons: sophisticated, expensive machines that at the time were closely-guarded tools of mass destruction. And there are many more out there from other governments like the Soviet Union which may never be found.

July 28, 1957 – Atlantic Ocean: An Air Force C-124 cargo aircraft that had taken off from Dover Air Force Base, Delaware lost power from two of its engines while flying over the Atlantic Ocean. Though the aircraft had two other engines, it could not maintain level flight, according to one report released in 2006 by the Department of Energy. The C-124 was carrying three nuclear weapons and one nuclear capsule at the time. Luckily, none of the weapons had the capsule installed, so none of the weapons could cause a nuclear detonation. With that in mind, the C-124 crew decided to jettison two of the weapons, perhaps to save weight and extend the aircraft’s range en route to an emergency landing near Atlantic City, New Jersey.

The crew jettisoned the first weapon at an altitude at 4,500 feet, and the second at 2,500 feet. The report said that both the weapons were presumed to have been damaged by the impact from such a great height and then submerged “almost instantly.” Meanwhile the aircraft landed safely with the remaining nuclear weapon and capsule aboard.

“A search for the weapons or debris had negative results,” reads the report, which noted that the ocean varies in depth in the area of the jettisons. One of the reasons this incident stands out from the rest on this list is that the aircraft involved was a transport plane, not a bomber or attack plane like the ones involved in many of the other events. Kristensen noted that today transport aircraft like the Air Force’s C-17 are the only jets allowed to fly America’s nuclear weapons when they need to be transported for inspection, replacement or redeployment. Flying may be the only option when transporting nuclear weapons to and from bases in Europe, but within the U.S., the government prefers to use trucks and trains since they are less risky than flight, Kristensen said.

The Department of Energy even has heavily modified tractor trailers complete with booby traps, immobilizing foam and tear gas designed to stop would-be thieves while transporting nuclear weapons by road. But don’t relax just yet, there is always a chance for something to go wrong. Kristensen noted that the U.S. still has thousands of nuclear weapons in about a dozen states, a handful of European countries, and aboard 14 Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines, so there are still plenty of possibilities for individual incidents.

“We don’t constantly fly them on B-52 [bombers] anymore, but there are still plenty of movements of nuclear weapons occurring,” Kristensen said.

Feb. 5, 1958 – Tybee Island, Georgia: An Air Force B-47 bomber was flying a training mission from Homestead Air Force Base Florida when, at 3: 30 a.m. while near Savannah, Georgia, the B-47 collided with an F-85 fighter jet. The B-47 pilot tried to land three times at nearby Hunter Air Force Base, Georgia, but the airplane was in rough shape, and it could not slow down enough to ensure a safe landing, the Department of Defense wrote in its list of nuclear weapons accidents. The pilot decided to ditch the Mark 15, Mod 0 nuclear weapon in Wassaw Sound, near Tybee Island, Georgia, rather than risk blowing up the base with the weapon’s 400 pounds of conventional explosives. Luckily, the nuke did not explode despite dropping from about 7,200 feet up. The B-47 landed safely, but the bomb was never found. Recovery crews searched a three-square-mile area using a ship, divers and an underwater demolition team wielding hand-held sonar devices. In 1998, a retired military officer and his partner also combed the sound with a Geiger counter but were also unsuccessful, the BBC reported earlier this month.

Today, the Department of Energy believes the 7,600 pound bomb is resting five to 15 feet under the seabed, according to a report shared by the BBC. The Department of Energy reported that there is no current or future possibility of a nuclear explosion, and the risk of a spread heavy metals is also low, but that could change if the bomb is disturbed. In other words, best to let sleeping nuclear dogs lie.

“[I]ntact explosive would pose a serious explosion hazard to personnel and the environment if disturbed by a recovery attempt,” the Air Force wrote in the report.

Sept 25, 1959 – Off the Washington/Oregon coast: A Navy P-5M, a flying boat designed for naval patrols and anti-submarine warfare, was carrying an unarmed nuclear anti-submarine weapon over the Pacific Ocean when it crashed in the sea about 100 miles west of the border between Washington and Oregon. Details about what led to the crash are scant, but the crew of 10 was rescued, according to the University of Southern California’s Broken Arrow Project. The nuclear weapons were not recovered, and while they did not contain any nuclear material, the weapons may still be somewhere on the ocean floor to this day.

Even if the nuclear weapons did not have nuclear material, could they be repurposed if found by bad actors? Kristensen reasoned that if the U.S. government with its abundant resources and intense focus when it comes to nuclear weapons cannot find the weapons off its own coast, then non-state actors or other countries such as Iran “have no chance to get them,” he said. “That’s just a fact.”

Indeed, the U.S. government is actually much more concerned with nuclear weapons being stolen from land-based sites rather than the few it has lost at sea. For