America is in an election year, but public opinion surveys these days seem to focus as much on Covid-19 as on who should be the next president. Pollsters use their survey data as a fuzzy form of viral tracking—noting, for example, that in March just 4 percent of Americans said they knew someone who had tested positive, versus 36 percent in June. Or they riddle us with findings like the one that says 65 percent of adults wear a mask in stores but only 44 percent report seeing others do the same. There’s even mashup polls that analyze pandemic partisanship: One from May announced that 74 percent of Republicans guessed they’d soon be back to a hair or nail salon, as opposed to 43 percent of Democrats and 55 percent of Independents. In short, while everyone was out buying pulse oximeters, the pollsters have been busy taking the nation’s pulse on the ever-changing public health emergency.

This endless surveying has gotten out of hand, and it needs to be reined in.

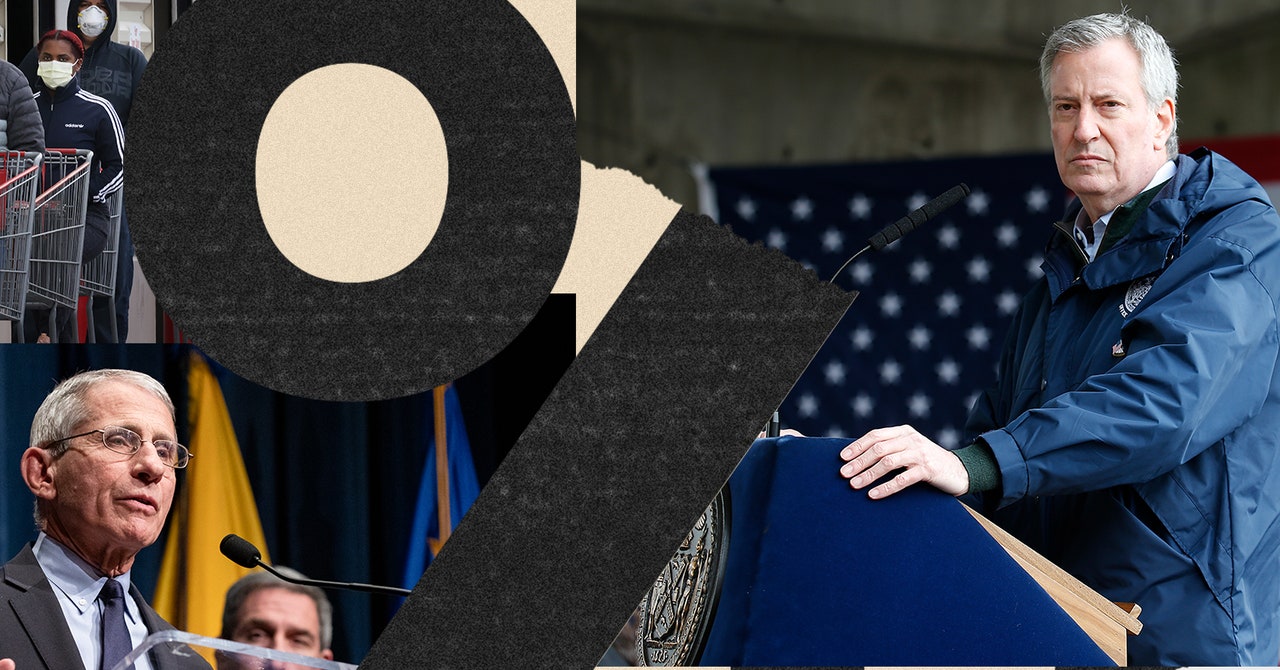

The Covid surveys aren’t simply grist for news reports; they appear to be a source of public health prescriptions at the highest levels of government. Just last week, New York City mayor Bill de Blasio nodded to the polls when he explained why the city’s schools would reopen. A survey of more than 300,000 public school parents by the city had found that around three-quarters wanted their kids back in the classroom this fall. “They feel ready now,” de Blasio said. “They know that’s what they want to do. So we’re full steam ahead for September.”

It’s as if we’re living in a game show where the public health option that gets the most applause wins. But this pandemic isn’t a game, and we need scientific expertise, not vox populi, to guide us. It may indeed be wise—and better for New York City’s public health—if schools reopen in the fall. To make that decision on the basis of a parent survey, though, as opposed to studies detailing how viral transmission can be curbed in classroom settings, suggests that the nation’s “leaders” are simply followers of their constituents.

Statewide policies on wearing masks seem to be similarly, and catastrophically, in thrall to public polling. Republican governors, such as Georgia’s Brian Kemp and Florida’s Ron DeSantis, may know of surveys showing that their voters are more reluctant to mask up. Gallup polls now find a 32-point gap, the largest that it has ever been, between the higher usage rates for Democrats and the lower ones for Republicans. In late June, Kemp explained why he wouldn’t issue a mandate: That “is a bridge too far for me right now. We have to have the public buy-in.” Around the same time, Florida governor Ron DeSantis said that, even though a mandate “could make an impact,” enforcing penalties “would backfire.” Wearing masks is no panacea, but in the aftermath of DeSantis’ comments, his state recorded 10,000 new coronavirus cases in a single day—marking the most significant jump in cases there since the pandemic began.

There is an argument to be made that surveys of public opinion on health measures can help policymakers manage outbreaks and communicate their messages more effectively. Polls of attitudes toward potential Covid-19 vaccines, for instance, could be used to plan for a massive immunization campaign. According to recent data from the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research, only 49 percent of Americans said they would take a vaccine against the new coronavirus, were one to become available, and one-fourth of surveyed Black Americans said they would. Public health officials can now unpack why that racial difference might exist and try to address it down the road.

But small differences in these kinds of polls can make a big difference in the headlines they generate—and the decisionmaking they inform. Whereas the Associated Press-NORC Center poll gave respondents the options of answering “yes,” “not sure” or “no” to receiving a hypothetical Covid-19 vaccine, a Pew Research Cente