Until recently, Guillaume Raineri, a forty-two-year-old man with a bald head and a bushy goatee, worked as an HVAC technician in Gonesse, a small town about ten miles north of Paris. The area lends its name to pain de Gonesse, a bread historically made from wheat that was grown locally, milled with a special process, and fermented slowly to develop flavor. The French élite once savored its crisp yet chewy crust and its tender, subtly sweet crumb. Raineri would occasionally grab a loaf from a boulangerie after work. He doesn’t consider himself a foodie—“but, you know, I’m French,” he told me.

After Raineri’s wife got a job at the National Institutes of Health, in Bethesda, Maryland, they moved to the U.S. The transition was something of a shock. “The food here is different,” he said in a heavy French accent. “Bigger portions. Too much salt. Too much sugar.” He decided to enroll in a paid study at his wife’s new workplace. It was exploring why the American diet, compared with almost any other, causes people to gain weight and develop chronic diseases at such staggering rates. “I wanted to know what is good for my body,” he told me.

In November, for four weeks, Raineri moved into a room that featured a narrow hospital bed, an austere blue recliner, and an exercise bike, which he was supposed to use for an hour a day. “It’s not as bad as it looks,” he said. His wife took to visiting him at the end of her shifts. Once a week, he spent a full twenty-four hours inside a metabolic chamber, a small room that measured how his body used food, air, and water. He was not allowed to go outside unsupervised, owing to the risk that he might sneak a few morsels of unsanctioned food.

Each day at 9 A.M., 1 P.M., and 6 P.M., Raineri was given an enormous meal—about two thousand calories—and instructed to eat as much as he liked. During the first week, he was offered minimally processed foods such as salad, vegetables, and grilled chicken, and he felt great. But, every Friday, researchers changed his diet. He was soon eating calorie-dense, processed foods that, in his words, “just sat in my stomach”: chicken nuggets, fries, peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches. He developed heartburn and began to feel bloated, sluggish, and irritable.

A few days before Thanksgiving, I entered the imposing brick building known as the N.I.H. Clinical Center, the world’s largest hospital dedicated to scientific research. I crossed its cavernous atrium, bought a granola bar (organic expeller-pressed canola oil, soy lecithin, soluble tapioca fibre) at an in-house coffee shop, and took a bite in the elevator. Then I followed Emma Grindstaff, a research assistant, to Raineri’s room.

Raineri was sitting in bed, scrolling through his phone in pale-blue pajamas; biometric activity bands were wrapped around his waist, wrist, and ankle. It was almost time for his daily “resting-energy-expenditure test,” to gauge how his metabolism was changing from one diet to the next. Raineri lay down; Grindstaff dimmed the lights and fitted what looked like an astronaut’s helmet around his head. By measuring what Raineri breathed in and out, a machine could approximate how many calories he was burning, and how many of those calories came from carbohydrates versus fat. (Breaking down fat takes more oxygen than breaking down carbs, and research suggests that people metabolize more fat on a less-processed diet.) A monitor estimated that he’d burn around seventeen hundred calories if he lay in bed for the rest of the day.

After the test, Raineri’s extra-large breakfast was rolled in on a cart. Because observation can influence a person’s eating habits, I was asked to leave. (You might skip that extra donut if someone’s watching.) He got to work on a veggie omelette, tater tots, and a jug of milk that contained added fibre.

In the past half century, nutrition scientists have blamed health conditions such as obesity, diabetes, and heart disease on many features of the American diet, including sugary beverages and saturated fat. These factors surely contribute to Americans’ uniquely poor health. But Kevin Hall, the N.I.H. study’s principal investigator, was researching a possible culprit that wasn’t named until the twenty-first century: ultra-processed food. The problem, Hall believed, might have less to do with high levels of sodium or cholesterol than with industrial techniques and chemical modifications. From this perspective, homemade jam on pain de Gonesse would be fine; Smucker’s on Wonder Bread would not, even if it contained less sugar and fat. “The thesis is that we’ve been focussing too strongly on the individual nutritional components of food,” Hall told me. “We’re starting to learn that processing really matters.”

In recent years, dozens of studies have linked ultra-processed fare to health problems such as high blood pressure and heart attacks, and also to some problems that one might not expect: cancer, anxiety, dementia, early death. One analysis found that women who ate the most ultra-processed food were fifty per cent more likely to become depressed than those who ate the least; another found that men who consumed more had substantially higher rates of colon cancer. (Most of these studies controlled for confounding factors such as income, physical activity, and other medical conditions.)

A focus on a food’s level of processing can lead to odd conclusions, however. Julie Hess, a research nutritionist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture, has pointed out that “ultra-processed food” puts canned kidney beans and gummy bears into the same category. Processing also has some benefits. It prevents food from going bad or being contaminated during storage and transport; it allows more people to eat convenient and varied meals, even when particular foods are not in season; and it helps the world feed a growing population. Walter Willett, a Harvard professor who may be the most cited nutrition researcher in the world, argues that studies like Hall’s are “worse than worthless—they’re misleading.” (He prefers to focus on the combinations of foods that people eat over time, and advocates for plant-based whole foods and the Mediterranean diet.)

While Raineri was having breakfast, I went down to a “metabolic kitchen” in the basement, which looked like a chemistry lab in the back of a restaurant. Raineri’s lunch and dinner were already being prepared; chicken breasts sizzled on a stovetop, and the smell of fried potatoes made my stomach growl. “A lot of chefs like to be creative,” Merel Kozlosky, a woman in a blue baseball cap who serves as the kitchen’s director, told me. “What we’re looking for is people who’re meticulous about following instructions.”

Hall and his colleagues had developed exacting protocols so that less-processed meals would closely match ultra-processed meals in terms of nutrients like salt, sugar, protein, and fat. This was meant to isolate the effect of processing. Tomato slices and lettuce leaves sat on a scale, which weighed food to the nearest tenth of a gram; a large stopwatch, for keeping track of cooking times, ticked nearby. Instructions on a clipboard explained how much Pacific Foods vegetable broth to add to soups A1 through E1, whose salt contents ranged from 0.39 grams to 5.61 grams.

I asked a tall, brown-haired cook which diet he most likes to prepare. “Preparing a day’s worth of ultra-processed meals might take an hour,” he said. “Unprocessed meals could take three or four times as long.” He brought his knife down forcefully, cleaving a carrot in two, and continued: “If I’m swamped, I’d rather make the ultra-processed menu. But if I had to pick one to eat for the rest of my life? Unprocessed, no question.”

A central question of the study is whether, consciously or unconsciously, participants eat more when they’re given ultra-processed foods—and, if so, why. This is why participants are offered such immense portions and can stop whenever they want. At one point, Kozlosky pulled a tray out of a commercial refrigerator. The meal looked as though it could feed a family of four: a tub of salad, a bowl of dressing, a container of beans, a cup of salsa, some shredded cheese, a wild-rice blend, and two pitchers of seltzer. After a meal, researchers weigh each dish to see how much has been eaten.

“Is this processed or unprocessed?” I asked.

Kozlosky smiled. “Ultra-processed,” she said. “Lots of participants can’t tell the difference.”

The term “ultra-processed food” was introduced by a Brazilian epidemiologist named Carlos Monteiro. In the early seventies, Monteiro was a primary-care doctor in the Ribeira Valley, an impoverished part of rural Brazil, and he treated many plantation workers with swollen bellies, stunted growth, and exhaustion. He started to think that they needed better food, in larger quantities, more than they needed medicine. He relocated to São Paulo, hoping to study malnutrition. Then he learned that around a million Brazilians were growing obese each year. Strangely, a shrinking number of people were buying ingredients that doctors blamed for the obesity epidemic, such as salt, sugar, and oil. The paradox troubled him.

In the nineties, many nutrition researchers began to turn their focus away from individual nutrients (antioxidants are good, saturated fat is bad) and toward broader dietary patterns. Monteiro developed a theory. Households that bought less salt weren’t eating less salt. They were no longer cooking. A growing share of their meals arrived in a package. “The issue is not food, nor nutrients, so much as processing,” he wrote in a landmark 2009 paper. Novel behavioral and brain-imaging experiments were showing that eating wasn’t always under our conscious control. Monteiro reasoned that something very bad had happened when industrial food systems started churning out cheap, convenient, and tempting foods. He argued that scientists should classify foods by their most unnatural ingredients and by their means of production.

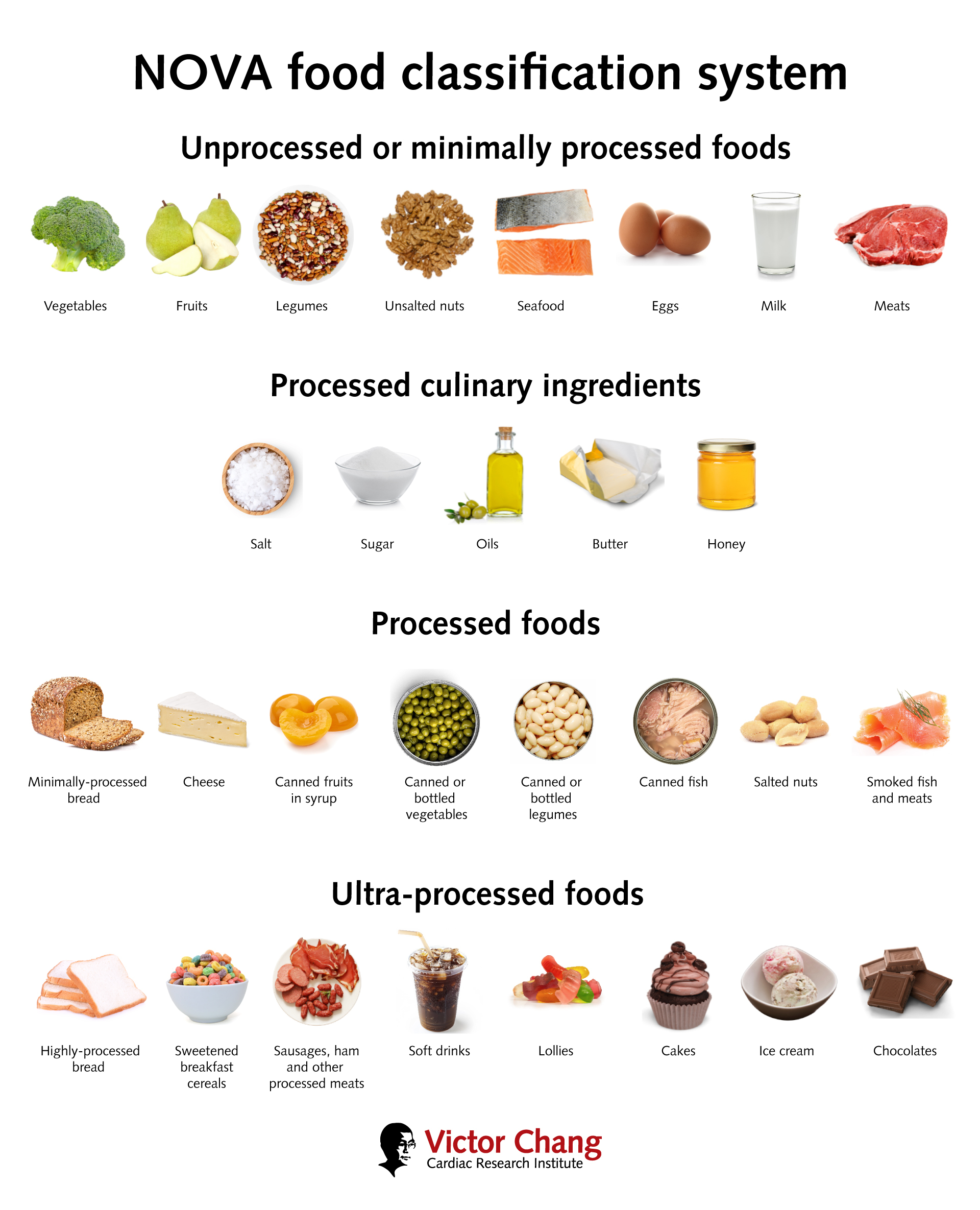

Almost all our food is processed in some way, but it matters how and how much. According to Monteiro’s NOVA Food Classification System, Group 1 foods are unprocessed or minimally processed: nuts, eggs, vegetables, pasta. Group 2 includes everyday culinary ingredients: sugars, oils, butter, salt. Butter and salt your pasta, and you have a Group 3 food: processed, but not automatically unhealthy. But add a jar of RAGÚ Alfredo sauce—with its modified cornstarch, whey-protein concentrate, xanthan gum, and disodium phosphate—and you’re biting into Group 4 ultra-processed fare. The ingredients of a Group 4 meal tend to be created when foods are refined, bleached, hydrogenated, fractionated, or extruded—in other words, when whole foods are broken into components or otherwise chemically modified. If you can’t make it with equipment and ingredients in your home kitchen, it’s probably ultra-processed. (Monteiro’s rubric did not account for industrially farmed crops and livestock, whose use food companies do not necessarily disclose.)

Monteiro’s peers were not immediately convinced. In the five years after his 2009 paper, there were essentially no scientific studies linking food processing to ill health. It wasn’t clear that his rubric had any more validity than the food pyramid, recommended dietary plates, or the nutrition traffic lights that are used in the U.K. But, gradually, scientists started to test his theory. In 2015, Hall, the N.I.H. researcher, attended a conference on obesity and presented research into low-fat and low-carbohydrate diets. After he left the podium, some Brazilian nutritionists approached him. “ ‘That’s a very twentieth-century way of thinking,’ ” he remembers them telling him. “ ‘The problem is ultra-processed food.’ ” The term sounded nonsensical. Nutrition is about nutrients, he thought. What does processing have to do with it?

Hall, who has short salt-and-pepper hair and often wears a lab coat, originally trained as a physicist. He became fascinated with nutrition after learning to model diseases at a Silicon Valley startup; while in a similar role at the N.I.H., he started working in a “metabolic ward” that was being built to study diet and exercise. Some of his early research examined metabolic changes in contestants on NBC’s “The Biggest Loser,” who’d lost drastic amounts of weight. After the Brazilian nutritionists told him about their theory, he designed a trial that he thought would discredit it.

In a study published in 2019, Hall invited twenty people to spend a month at the N.I.H. Clinical Center, where his team measured how their bodies responded to different types of food. (Many researchers rely instead on surveys of what people recall eating.) For two weeks, participants ate a minimally processed diet, mostly consisting of Group 1 foods such as salmon and brown rice; for the other two weeks, they ate an ultra-processed diet. At least eighty per cent of the calories came from Group 4 foods.

Hall ended up refuting his own hypothesis. When participants were on the ultra-processed diet, they ate five hundred calories more per day and put on an average of two pounds. They ate meals faster; their bodies secreted more insulin; their blood contained more glucose. When participants were on the minimally processed diet, they lost about two pounds. Researchers observed a rise in levels of an appetite-suppressing hormone and a decline in one that makes us feel hungry.

It wasn’t clear why ultra-processed diets led people to eat more or what exactly these foods did to their bodies. Still, a few factors stood out. The first was energy density—calories per gram of food. Dehydration, which increases shelf life and lowers transport costs, makes many ultra-processed foods (chips, jerky, pork rinds) energy-dense. The second, hyper-palatability, was a focus of one of Hall’s collaborators, Tera Fazzino. Evolution trained us to like sweet, salty, and rich foods because, on the most basic level, they help us survive. Hyper-palatable foods—combinations of fat and sugar, or fat and salt, or salt and carbs—cater to these tastes but are rare in nature. A grape is high in sugar but low in fat, and I can stop eating after one. A slice of cheesecake is high in sugar and fat. I must eat it all.

In certain areas, these findings defied the logic of earlier theories of nutrition. If the goal was to minimize processing, then a diet that includes butter might be healthier than one that includes margarine, and one that includes cane sugar might be healthier than one that includes zero-calorie sweeteners. The occasional whole egg, which contains more than half the daily recommended dose of cholesterol, might be preferable to packaged liquid eggs, which are protein-rich and sometimes cholesterol- and fat-free, but often contain preservatives and emulsifiers.

It’s common to think about the obesity epidemic, which contributes to nearly three million deaths around the world every year, in terms of energy imbalance. Sometime in the middle of the twentieth century, the story goes, we started to consume more calories than we burned, and thus we gained weight. There are good reasons to subscribe to this view; feed virtually any animal extra food and it will gain weight. But research has increasingly complicated the “It’s the calories, stupid” model of obesity. Our bodies process carbs differently from fats, for instance; a calorie from corn leads your body to secrete more insulin than a calorie from cheese. Certain food additives seem to activate genes associated with weight gain, and things like weight loss and exercise can reset the body’s metabolic rate. “The dirty little secret is that no one really knows what caused the obesity epidemic,” Dariush Mozaffarian, a dean at the Tufts School of Nutrition Science and Policy, told me. “It’s the biggest change to human biology in modern history. But we still don’t have a good handle on why.” If anything, Americans began consuming slightly fewer calories after the turn of the twenty-first century, according to national survey data, yet rates of obesity continued to climb. (Obesity rates in the U.S. may now be falling, possibly owing to the introduction of GLP-1 drugs such as Ozempic, but they remain the highest in the industrialized world.)

Before reuniting with Raineri, I sat down with Katherine Maki, a clinician and microbiome researcher who is working with Hall, in the atrium. Maki leads what she calls the “poop squad,” which analyzes stool samples to understand how various diets influence the bacteria in our gut. (Such studies have been in vogue for the past decade or so, although it has often been difficult to figure out the separate contributions of thousands of kinds of bacteria and to put the studies into clinical practice.) “The foods we eat leave a bacterial signature inside our bodies,” Maki said. “We’re getting better at decoding that signature.” I bit into the remains of my granola bar.

One bacterium, B. theta, ordinarily helps us digest fibre. But if we don’t get enough fibre—and ninety-five per cent of Americans don’t—it starts to feed on mucus instead. “Think of it as eating the lining of your gut,” Maki said. “Not good from an inflammation standpoint.” Some of the artificial sweeteners in zero-calorie sodas and “no-sugar-added” desserts, such as saccharin and sucralose, appear to shift the microbiome in ways that impair the body’s handling of sugar. The spread of the Western diet has coincided with striking declines in microbial diversity. Some of our gut bacteria have disappeared altogether.

There are also bacteria on our skin, and they, too, can be affected by what we eat (as well as by things like cosmetics and soaps). The skin microbiome has been linked to increasingly widespread conditions such as acne and eczema. In November, a study reported that ultra-processed foods may cause flares of psoriasis. And so, after breakfast, Raineri donned a hospital gown in the Clinical Center’s dermatology wing.

“When was the last time you showered?” a dermatologist asked him.

“Yesterday at eleven,” Raineri said.

“11 A.M. or 11 P.M.?”

“Ah, A.M.,” he said.

The dermatologist seemed satisfied that he was sufficiently dirty. She taped several strips to his forehead and under a tattoo on his back. These would measure the amount of fat that his glands secreted on that week’s diet. Then she swabbed several body parts. I didn’t need the concept of ultra-processed foods to suspect that last week’s oily tater tots had produced the pimple on my forehead, but I wondered what other changes they might have wrought.

“I take things one centimetre at a time.”

Cartoon by Amy Hwang

Scholars of obesity sometimes point out that since the epidemic began humans haven’t had time to evolve as a species—our food must be to blame. This is true, but incomplete, because the foods we consume change our biology. Highly processed diets might reduce the sensitivity of taste receptors, for example, which could mean that we eat more to get the same hit. Taste presumably evolved to gauge the nutritional content of food, but ultra-processed products don’t need to be nutritious to taste good. “With a physiological confusion that barely makes it to the surface of our conscious experience, we find ourselves reaching for another—searching for that nutrition that never arrived,” the physician Chris van Tulleken writes in his recent book, “Ultra-Processed People.” Some scientists have proposed “taste-bud rehab” to redirect our cravings toward healthy options.

In the afternoon, I joined Raineri for a taste test. The aim was to understand how quickly his preferences shifted when his diet changed—whether fries and chicken tenders made his taste buds crave more salt, for instance. Raineri sat down at a large table; an opaque shield blocked his view of medicine bottles that contained various solutions of salt and sugar. A nurse poured two solutions into paper cups. Raineri swished the first in his mouth, apparently unperturbed, and spit it into a bright-blue bag. But the second made him grimace and stick his tongue out, as though he were sitting through the worst wine tasting ever.

Hall’s original study, which has been cited nearly two thousand times, was the first randomized trial demonstrating that ultra-processed foods disrupt our metabolic health and lead people to overeat. It was hugely influential and is widely recognized as the most rigorous examination of the subject so far. “It got the most attention of any study I’ll probably ever do,” Hall said. It also sparked controversy and opposition. By necessity, the study was conducted in a highly artificial environment. Some of its findings might not have persisted; in the second week that participants ate an ultra-processed diet, for example, their excess calorie consumption started to fall.

One of the largest studies of ultra-processed foods, led by researchers at Harvard—including Willett, the critic of Hall’s study—divided ultra-processed foods into ten subgroups. (The study was based on survey data from more than two hundred thousand people, rather than a double-digit number of people in metabolic chambers.) Its conclusions were more complicated than Hall’s. Two types of ultra-processed foods (sugary sodas and processed meats) increased people’s risk of cardiovascular disease, but three types (breads and cold cereals, certain dairy products such as flavored yogurts, and savory snacks) seemed to decrease their risk. Another five didn’t appear to affect it at all. “Some food additives are good, some are bad, most are probably neutral,” Willett told me. Last month, a committee of twenty nutrition experts released its recommendations for updating the U.S. dietary guidelines; it declined to endorse broad limits on ultra-processed foods, calling the currently available evidence “limited,” but suggested that people avoid processed meats.

Talking to skeptics of Monteiro and Hall, I found myself vacillating between excitement about the utility of a burgeoning theory and pessimism about its seeming futility. “All of this research is a colossal waste of money,” Alan Levinovitz, a professor at James Madison University and the author of “Natural: How Faith in Nature’s Goodness Leads to Harmful Fads, Unjust Laws, and Flawed Science,” told me. “We already know why populations are gaining weight: ubiquitous, cheap, delicious, calorie-dense foods.” He called it “appalling that we’ve turned this into some kind of research question when the answer is staring us right in the face.” He had a point; many of Monteiro’s recommendations can arguably be summed up with seven words from “In Defense of Food,” the 2008 book by Michael Pollan: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.”

Even as more studies bolster Monteiro’s theory of ultra-processed foods, it remains unclear whether any of them will change what we eat. People know that Doritos are not so good for them, but more than a billion bags are sold in the U.S. each year. Who, exactly, will be moved by the knowledge that salty-sweet ultra-processed foods might be worse than merely salty or sweet ones? Our food environments—the type and quality of food that pervades our schools, workplaces, and neighborhoods—influence our diets as much as our tastes do. And our food environments are shaped by our incomes, our government’s choices, and our desire for convenience, as well as active manipulation by the food industry, through things like marketing campaigns and lobbying for agricultural subsidies. During my medical residency, I often urged patients with diabetes or heart disease to eat healthy foods, only to scrounge my own dinner from onion rings and chicken tenders in the hospital cafeteria.

Hall argues that research into ultra-processed foods, which make up an estimated two-thirds of the American diet, could prove useful to the very companies that manufacture them. “Industry is just as happy to sell you a healthy version as an unhealthy one,” he told me. But Big Food is adept at contorting nutrition science to promote its products. “The idea that you’re going to get companies to reëngineer their products in this or that way is, I think, totally misguided,” Gyorgy Scrinis, who coined the term “nutritionism” to describe reductive, nutrient-focussed approaches to food, told me. The makers of ultra-processed breakfast cereals can describe their products as “part of a balanced breakfast” if they add some fibre; Vitamin Water is marketed as a health drink even though a twenty-ounce bottle contains almost as much sugar as a can of Coke.

Of course, since no previous theory has succeeded in halting or even fully explaining the obesity epidemic, we need new ideas. “It’s long past time that the scientific community seriously considered alternate hypotheses,” Mozaffarian, the Tufts dean, told me. (He thinks that ultra-processed foods have probably contributed to rising obesity rates and suspects that biological changes—such as alterations in our microbiomes, metabolisms, and epigenetics—have played a role, too.) Historically, there have been separate movements against sugary sodas, fast food, and harmful additives, but a concept like ultra-processed foods could unify politicians, parents, and public-health professionals around a single health campaign. Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., who may soon lead the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, has made common cause with some lawmakers by railing against ultra-processed food, pledging to remove it from public schools and limit the use of pesticides, artificial dyes, and, perhaps more dubiously, seed oils. “We need to stop feeding our children poison and start feeding them real, wholesome food again,” he posted on X in November. (Kennedy’s collaborators will need to navigate his thicket of unfounded claims about viruses, vaccines, and wellness fads.) Some experts want to eliminate agricultural subsidies for corn and soy; others have advocated for a tax targeting ultra-processed products, which is being tried in Colombia, or marketing restrictions, which have been introduced in Chile.

Shortly after I visited the N.I.H., Hall flew to London to present preliminary findings from the first eighteen participants in his study. He told the audience that his team was testing the effects of four diets: one that was minimally processed and three that were ultra-processed but varied in terms of calorie density and hyper-palatability. “Now, the drum roll,” Hall said. The audience laughed as he pulled up a color-coded slide.

When people were fed an ultra-processed diet that was calorie-dense and hyper-palatable, they ate around a thousand calories more per day than they did on the minimally processed diet. When the team served foods that were calorie-dense but less palatable, participants still ate about eight hundred calories more. But when the team served ultra-processed foods that were neither calorie-dense nor hyper-palatable—for example, liquid eggs, flavored yogurt and oatmeal, turkey bacon, and burrito bowls with beans—people ate essentially as much as they did on the minimally processed diet. They even lost weight. A murmur rippled through the crowd. Calorie density, probably the feature of food that had the biggest impact on our ancestors’ survival, now seemed to be among the most responsible for making us overeat. “Weight gain is not a necessary component of a highly ultra-processed diet,” Hall concluded. He had, in a sense, refuted his hypothesis again.

While reporting this story, I became obsessed with checking nutrition labels, but I don’t think that I managed a single day without eating an ultra-processed food. I’d order a salad and the dressing would contain preservatives; I’d pick up a parfait and would be felled by a sweetener in the granola. My own medical tests border on prediabetes, and I try to cook healthy dinners for my three kids. But I often acquiesce to their demands for pizza, saving myself not only time but negotiations over every broccoli floret (eat four if you’re four, two if you’re two, and so on). With fries, I have to negotiate with them to stop. In the moment, these concessions feel inescapable and inconsequential. Afterward, while sitting up in bed with reflux, I worry about the example I’m setting and resolve, again, to do better.

On a warm November afternoon, at a cozy French café in lower Manhattan, I met up with a person who, I hoped, might restore a sense of perspective. Marion Nestle, a towering figure in American nutrition, is a molecular biologist and nutritionist who started the country’s first academic food-studies program, at N.Y.U., helping to bring attention to the roles that culture, capitalism, and politics play in what and how much we eat. (She pronounces her last name like the verb, not the world’s largest food-and-beverage company.) Now in her late eighties, she bounded up the stairs to the café entrance, her curly gray hair bobbing. At the counter, she ordered black tea with whole milk; I got a drip coffee and, as a provocation, a large chocolate-chip cookie.

We sat down at a table, and I placed the cookie on a napkin. “Pretty ultra-processed, right?” I said.

“Butter, sugar, flour, eggs,” she said. “Actually, I think it’s probably O.K.” She broke off a piece and popped it into her mouth. (In other ways, she noted, cookies are not exactly healthy.)

“You’ve got to understand how we got here,” Nestle said, launching into a monologue about the evolution of nutrition science. In her telling, the first era began in the early twentieth century, after the discovery of vitamins. During the Second World War, U.S. military leaders were alarmed that many recruits, having grown up during the Great Depression, couldn’t join the war effort because of conditions caused by a lack of nutrients, such as rickets, scurvy, anemia, and tooth decay. “That came as a shock, and the military became heavily concerned with nutrition,” she said. It partnered with the National Academy of Sciences and the National Research Council, which together published the first recommended dietary allowances for various nutrients.

Nestle sipped her tea. The second era began in the years after the war, she said, when heart disease was emerging as a leading killer. In the mid-twentieth century, around the time that scientists were identifying plausible dietary culprits—salt, fat, cholesterol—Nestle’s father died of a heart attack. In the late seventies, a Senate committee led by George McGovern issued a report calling on people to consume less dairy and red meat. But, after blowback from industry, the guidance was reworked to emphasize nutrients (in this case, saturated fats) instead of foods. “Eating less is very bad for business,” Nestle said. She argues that this act of appeasement cast a long shadow. “Even today, when people talk about what we need to eat more of, they talk about food,” she said, her voice rising. “But when they talk about what we need to eat less of, they switch to nutrients!” She pounded the table; a couple seated next to us glanced over.

How nutrients find their way into our bodies matters. Sugar in Skittles isn’t the same as sugar in strawberries; fish oil in a capsule isn’t fish oil in a fish. The third era of nutrition has considered dietary patterns more holistically. We talk more of the Mediterranean diet and less about the fat in olive oil. Nestle believes that Monteiro and Hall have revolutionized the field by narrowing in on what about our diets leads us to overeat. The theory of ultra-processed foods “has some frayed edges,” she told me, but it offers ordinary people a practical way to make decisions about what to eat. “As an organizing principle, it’s invaluable.”

Nestle and I took a sunset stroll, past a street vender selling hot dogs (beef, salt, sorbitol, potassium lactate), to a nearby grocery store. She jabbed her finger at the nutrition label on a bright-green box of Apple Jacks. “This is where it starts,” she told me. “Hydrogenated coconut, modified food starch, degerminated yellow corn flour, yellow six, red forty, blue one.” She shook her head and said, “Yuck, yuck, yuck! This is what we’re feeding our kids.”

She lifted up a box of Shredded Wheat. “Now this is the good stuff,” she said. There were two ingredients: whole-grain wheat and wheat bran. “I sprinkle a little sugar over it,” she confided with a wink. “That way I get to control how much sugar I’m eating—not some corporation.”

In the dairy section, Nestle compared a whole-fat yogurt (milk, bacterial cultures) with a low-fat version (milk, bacterial cultures, cornstarch, and pectin, among other things), whose emulsifiers and thickeners improved creaminess and mouthfeel. “See, it can be tricky,” she said. It hadn’t occurred to me that yogurt with more fat could be healthier than yogurt with less. Still, Nestle told me, “it matters how ‘ultra’ the ultra-processing is. This yogurt will never be a bag of Doritos.” The former was food—it retained the links between taste and nutrients which our bodies evolved to expect—with some additives. The latter (corn, vegetable oil, maltodextrin, a string of flavorings and other additives) seemed to be substantially made up of industrial ingredients and only partly made of food.

On our way out, we stopped by the bread aisle, and Nestle noted that many whole-wheat breads, including a brand that I’d recently started buying, were ultra-processed. Some used highly processed flours that are cheaper and easier to work with, but are stripped of nutrients such as fibre and minerals. I thought about something that Willett, the Harvard professor, had told me. He and several of his colleagues enjoy the same kind of whole-grain bread from Trader Joe’s. “It’s made in a factory,” he’d said. “It’s ultra-processed. But to say it’s unhealthy just because of that is frankly ridiculous.”

“It’s perfectly possible to make bread that isn’t ultra-processed,” Nestle told me. “But it doesn’t last as long.” She read from the label of a healthy-looking loaf. “DATEM!” she declared, referring to diacetyl tartaric acid esters of mono- and diglycerides of fatty acids, an emulsifier that helps bread maintain its structure. “Forget about it.”

A few weeks later, I drove an hour and a half east from Manhattan to the headquarters of Seviroli Foods, one of the largest pasta manufacturers in the world. Seviroli produces more than seventy-five million pounds each year and specializes in stuffed pastas such as ravioli and tortellini. Its factory encompasses an entire city block, with separate buildings devoted to pastas and sauces.

When I arrived, Franco LaRocca, a gregarious man who works as the company’s corporate chef and vice-president of research and development, told me that his parents migrated from southern Italy to Brooklyn in the early seventies. Growing up, he often awoke to the smell of his grandmother’s focaccia, which he’d dip in steaming tomato sauce; he later worked at Union Square Café. “I still want to make dishes that feel like you just ordered them at a fancy restaurant,” he told me.

I followed LaRocca to a part of the factory that was producing beef ravioli for the day. Before entering, we donned hairnets, safety glasses, and disposable gowns that reminded me of the early days of the COVID pandemic. I washed my hands, stomped my feet in white disinfectant powder, and entered a room that roared like a tarmac.

Enormous silver machines glinted under fluorescent lights. Workers milled about with clipboards and what looked like hardhats, as though they were making Toyotas rather than tortellini. A maze of metal pipes crisscrossed overhead, and LaRocca pointed to one of them, which terminated in a car-size funnel that hung from the ceiling. “That’s pumping in flour from the silos outside,” he explained over the din. We climbed up to a platform to get a better look.

The cone was dumping enriched semolina flour into a gigantic tank. Thick hoses piped in water and eggs. Dough exited onto a blue conveyor belt; a sheeter pressed it into a three-foot-wide carpet. Then a metal mold called a pasta die determined the shape of the ravioli: square, circle, half-moon. Finally, a piston pumped rhythmically up and down, topping the carpet with dollops of ground beef. Seviroli’s pasta was processed—it probably had to be, to meet the punishing scale and cost demands of a competitive market. I was trying to decide whether it also earned an “ultra.”

“The price we charge depends on how thin the shell is and how much filling is inside,” LaRocca told me. “The more delicate or unique the shape, and the higher the fill rate, the more it’ll cost you.” I watched ravioli slide into a horizontal cylinder, where it would be cooked. Lastly, it was shaken dry and passed into a freezer that was the size of a studio apartment. In the forty minutes that the process lasted, the company had made about six thousand pounds of pasta.

You could find features of ultra-processing if you looked: Seviroli’s cheese ravioli, for example, is mostly ricotta and enriched semolina flour, but it also contains guar gum, a stabilizer made from heavily processed beans, and cornstarch. Still, the company limits processing by cooking and immediately freezing pastas, minimizing the use of additives, and avoiding hydrogenated oils. When I described the factory to Nestle, she said, “Industrial alone does not an ultra-processed food make. It has to have the purpose of replacing real food . . . and, usually, to be loaded with additives.” (This doesn’t mean that frozen stuffed pasta—with its high levels of saturated fat, cholesterol, and sodium—should be eaten for every meal.)

Next door, workers were making the sauce for macaroni and cheese. Forty-pound blocks of Romano cheese sat on a pallet like bricks. Each one had a bar code and would be grated only after a work order had been placed. “Pre-shredded cheese spoils faster,” LaRocca said. “This way we can avoid preservatives.” A man pushed a buggy full of grated cheese onto a scale. It appeared to clock in at the right weight.

“It’s not exactly classic Italian,” LaRocca admitted. “But people love it.”

In another room, LaRocca used both hands to lift the lid from a cauldron that stretched ten feet into the air. Steam misted off a bubbling yellow lava; a buttery aroma filled my nostrils. “We add Asiago,” LaRocca said. “Gives it a nice aged note.” The vat piped its contents into a sort of vending machine for bags of sizzling cheese sauce, which passed through chilled water and into containers the size of dining tables. A forklift ferried some away. I was a little unsettled, but also astonished. Seviroli produced a nearly unfathomable amount of food at modest prices—a pound of spinach ravioli goes for six bucks—with reasonably high-quality ingredients. It seemed to exist on the boundary between ordinarily processed and ultra-processed, and it made me think that there was a middle way—one that, within the practical and economic realities of modern society, could keep people fed without making them sick.

Back in LaRocca’s kitchen, he fixed me a plate. The macaroni was al dente; the creamy cheese melted in my mouth. I finished it quickly but refrained from asking for more.

“It’s good!” I told him.

“Yeah,” he said. “But my daughter prefers Kraft.” ♦