In laboratory studies using brain tissue, oxytocin appeared to reverse the effect of a toxic protein associated with Alzheimer’s disease on brain cells. The hormone may restore the cells’ “plasticity,” which is vital for memory and learning.

The hormone oxytocin originates in a part of the brain called the hypothalamus. Oxytocin plays important roles in childbirth, breastfeeding, and social bonding.

It may also facilitate romantic attachment. The body releases the hormone during sexual activity, earning the chemical its popular reputation as the “love hormone.”

Oxytocin’s related role in social bonding suggests that it could also help treat social anxiety and autism.

Its effect on memory is less well-established, but an older study in mice found that it can improve long-term spatial learning and memory.

Recently, researchers at Tokyo University of Science in Japan and Kitasato University, also in Tokyo, Japan, wondered whether or not the chemical could help protect nerve cells in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia, affecting more than 5.5 million people in the United States alone and millions more around the world.

People with Alzheimer’s experience progressive memory loss and cognitive decline.

A leading theory proposes that the accumulation of clumps of a toxic protein called beta-amyloid in the brain causes Alzheimer’s. However, recent research has called this view into question.

One older study did find that injecting synthetic beta-amyloid into the brains of rats caused problems with learning and memory.

Another study, this time from 2000, found that when scientists perfused slices of rat brain in a dish with beta-amyloid, it inhibited “long-term potentiation” (LTP), which is the mechanism that allows nerve cells to encode memories.

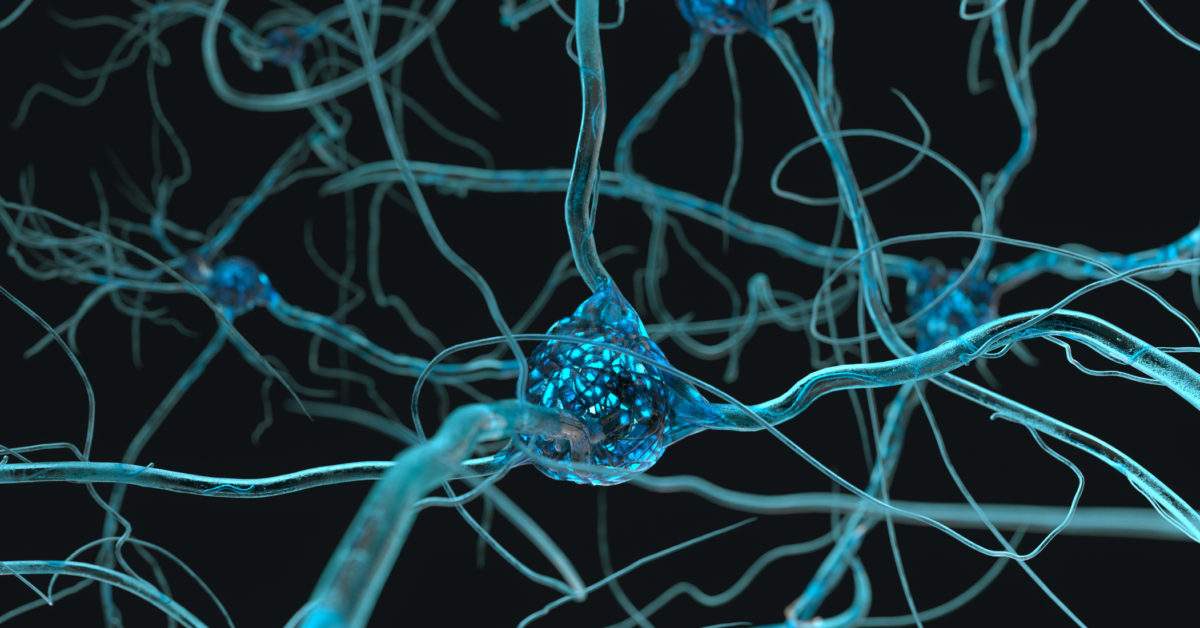

LTP occurs when different nerves fire simultaneously, strengthening the electrical connections, or “synapses,” that pass signals between them.

Beta-amyloid seems to impair nerve cells’ capacity to strengthen their synapses in this way, which neuroscientists refer to as their “plasticity.”

A part of the brain called the hippocampus, which is