A Powerade bottle from 2001 was found on Yaya, a Peruvian beach south of Lima. A Coca-Cola bottle from 2002 was found on Robinson Crusoe Island, a World Biosphere Reserve, in Chile. These were the oldest of all the bottles collected.

These discarded pieces of packaging were collected in a new macro-study that looked at the origin of plastic bottle pollution on beaches and cities along Latin America’s Pacific coastline. The research—the first to be conducted on a regional scale, thanks to a citizen science initiative covering 10 countries—combed more than 12,000 kilometers of coastline along the west coast of South and Central America. It found that across the region, Central American countries are most affected by coastal plastic pollution, and underscores the urgency of confronting this major problem.

Although volunteers found numerous bottles dating back more than a decade, “most of them were less than a year old,” says scientist Ostin Garcés, an expert on the impact of plastic on marine ecosystems at the University of Barcelona and a lead author of this new research.

Plastic makes up the majority of the garbage on coastlines around the world and has reached even the most inhospitable corners of the planet, including the deepest parts of the oceans and both the Arctic and Antarctic. Its impact not only has repercussions on biodiversity and the balance of ecosystems; various studies show how plastic already colonizes our insides, runs through our blood, and lives in our brains and organs. Microplastics have even been found in semen and ovaries. The microplastics that we eat, drink, and breathe every day are part of us.

An environmentalist searches for plastic waste and packaging dumped on El Esterón beach in Intipuca, El Salvador, in October 2024.

Photograph: MARVIN RECINOS/AFP via Getty Images

“Production and consumption continue unabated,” says Garcés, who is part of the team that sampled a total of 92 continental beaches, 15 island beaches, and 38 human settlements to determine the abundance, origin, and characteristics of plastic bottles along Central and South America’s Pacific coast. This study reveals surprising data, given that more than half of the bottles and caps collected had visible dates.

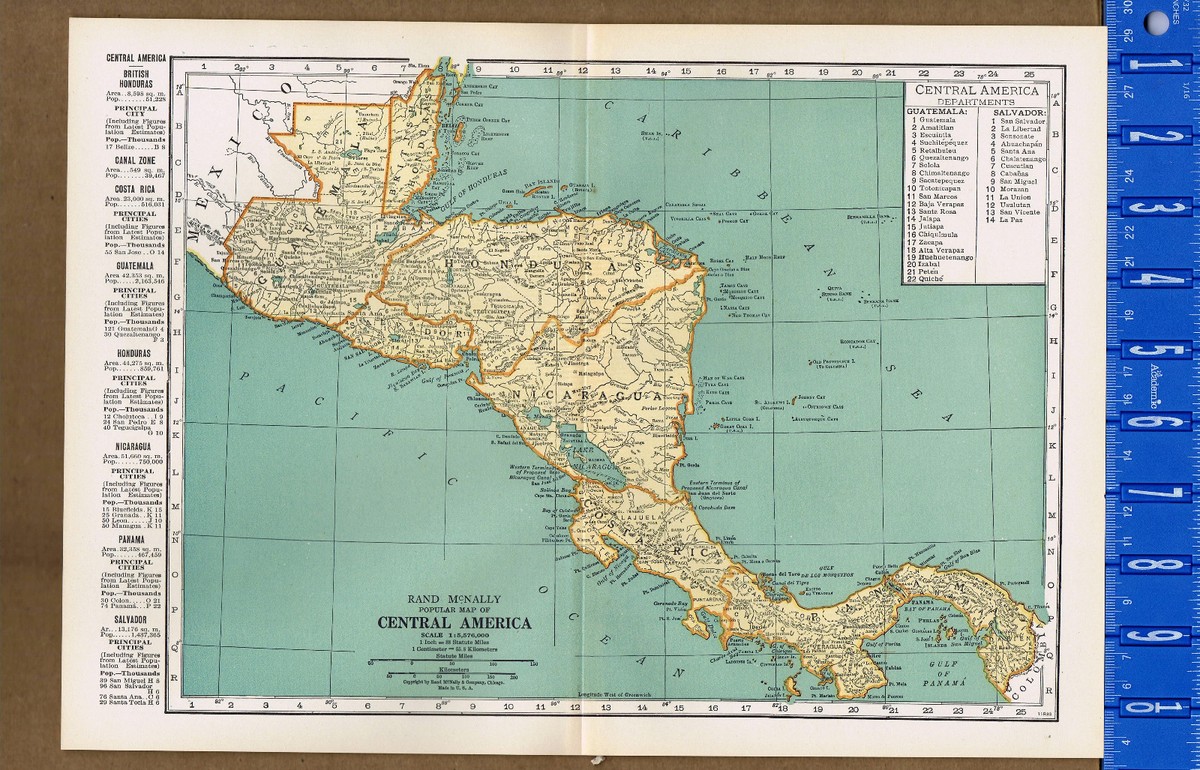

According to the study, containers for soft drinks, energy drinks, and drinking water were the most common. The countries with the highest rates of plastic bottle pollution were El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Guatemala, likely due to their coastal population density, high consumption of beverages in plastic containers, and poor waste management, the study’s authors argue. “These are countries that lack the necessary infrastructure and technical capacity [to control plastic bottle waste]. Therefore, all the beverage waste that reaches their communities ends up in nature,” says Garcés.

There is also another very important factor that is driving up pollution, Garcés says. “Our study shows rising temperatures have caused people in these tropical areas to consume more bottled beverages.”

The large number of plastic water bottles found in Central American countries is a symptom of another serious problem in the region, but one that affects most countries on the continent: limited access to safe drinking water, which drives people to buy bottled water and other packaged drinks.

Volunteers pick up trash and plastic debris on the beach and cliffs as part of a nationwide beach cleanup in Lima, Peru, in March 2025.

Photograph: Klebher Vasquez/Anadolu via Getty Images

The results reveal that almost 60 percent of the items with identifiable origins came from countries within the Latin American Pacific region itself—that is, from local producers. “They are manufactured by bottling companies located in the same country but that work with international brands, such as Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, and Aje Group,” explains Garcés. These three multinationals account for the majority of the collected bottles. Bottles from 356 brands produced by 253 companies were identified.

The study recorded information contained on the bottles and their caps—such as labels and engravings—to work out their manufacturer, production date, and place of origin. This allowed the researchers to identify sources of pollution and the journeys taken by individual items to reach the beach or city where they were collected.

While continental beaches were filled with local products, island beaches receive many Asian bottles, likely arriving from ships and via ocean currents. This observation, Garcés says, was precisely what prompted the research he participated in. In 2023, the Trash Scientists Network, a program of Universidad Católica del Norte in Chile, conducted a study that showed that many bottles that end up on remote islands, such as Rapa Nui (Easter Island) or the Galapagos, had letters on their labels that were not in Spanish, but in Chinese or Japanese. “That’s where the idea of investigating where those bottles came from came from,” Garcés says.

An image from the study illustrating how plastic bottles reach Latin American Pacific coasts.

Illustration: Garcés-Ordóñez et al. (2025) (CC BY 4.0)

The scientists found that, like other marine debris, the bottles and caps they retrieved were sometimes colonized by immobile organisms called epibionts, which live on the surface of other organisms or materials. The team found items with bryozoans, barnacles, and mollusks attached, with the presence of these correlating with the age of the plastic. Bottles and caps also exhibited degradation patterns typical of marine exposure—discoloration, wear, and fragmentation.

However, despite these transformations, the plastic waste often retained key identifying characteristics, such as product codes, brand names, manufacturing locations, and dates. This data helped trace their provenance, even when bottles were damaged or heavily colonized by organisms, providing valuable information about their origin and transport pathways.

For Garcés, one of the most worrying conclusions of his study is the situation on islands like the Galapagos and Rapa Nui, protected natural areas. As he explains, epibionts attached to the plastic bottles are washing up on their beaches, “and that represents a serious threat, because we don’t know what species of organisms are arriving or where they’re coming from. And they can be invasive.”

The work would not have been possible without the collaboration of up to 200 local leaders from 74 social organizations, as well as the 1,000 volunteers who were part of this citizen science initiative. Their methodological approach not only allowed the research team to better understand the characteristics of the plastic waste affecting the Latin American Pacific, but also to understand regional beverage preferences and consumption trends in different countries.

Proposals to Solve This Crisis Given the widespread presence of disposable plastic bottles, mainly of local origin, one of the researchers’ main recommendations is to replace them with standardized returnable bottles throughout the region—“like we used to do,” Garcés says. “When I was a kid, products were sold in returnable glass bottles. This would be one of the main measures we propose to reduce the production of plastics from the source.”

This measure, he says, should be complemented by refund policies and corporate social responsibility initiatives on the part of the beverage companies involved. Demanding reusable packaging and accountability from large producers of bottled drinks are essential strategies to reduce plastic pollution and protect coastal ecosystems, say the authors. “In the end, companies have their own interests and look for the cheapest alternatives for bottle production. That is why governments have to get involved,” says Garcés. However, he says that improving waste management, especially in coastal communities, is another key issue that needs to be addressed.

The researchers also highlight the central role of human behavior in reducing plastic pollution. “As we grow as a population, consumption increases. And, as long as the basic needs of coastal populations in terms of access to drinking water are not met, it will continue to increase, contaminating more and more coastal environments,” Garcés says. When drinking water is only available in single-use plastic bottles, consumers have no alternatives, “limiting their ability to act sustainably.”

This story originally appeared on WIRED en Español and has been translated from Spanish.