This story is part of our ongoing “First Steps” series, where we share extraordinary stories of men who transformed their bodies, minds, and lives with a focus on the first steps it took them to get there (because, after all, nothing can change without a first step!). Read all of the stories here.

Scott Strode, 51, started drinking at 11 and using cocaine by 15. Addiction consumed his early 20s, leaving him paranoid and fearing an overdose. Once he got sober, fitness—climbing, boxing, triathlons—became his refuge. Determined to use his experience to help others, in 2006 he founded The Phoenix, a sober active community that has helped over half a million people overcome addiction. His forthcoming memoir, Rise. Recover. Thrive., aims to inspire even more people on their journey to recovery. In his own words, here’s how he did it.

I GREW UP in rural Pennsylvania and had a father with untreated mental health struggles. He once tore out an exterior wall of our house during a manic episode and never rebuilt it. He just stapled plastic up, so we lived in a house with three walls. Our house had an outhouse and no heat. We barely had running water.

I lived a very different life with my mom, who was a very accomplished businesswoman. She ended up becoming a U.S. ambassador and was friends with three different presidents. But she remarried, and my stepfather struggled with alcohol.

Mine was a pretty dynamic childhood. I didn’t know it at the time, but it was causing some significant self-esteem wounds. When I discovered drugs and alcohol during my adolescence, they helped some of that pain go away. So I jumped in with both feet.

I drank my first beer at 11. Everybody I looked up to at that point—my cousins, people in my stepfather’s family–regularly imbibed from a keg or liquor cabinet. When I told my friends about it, they all lit up. I realized people wanted to be around me to hear that story, and I thought, we have a fridge full of beer in the garage. I could grab a couple. All of a sudden, everybody wanted to hang out at my house, and I started connecting with others in a way I was craving.

I started throwing a lot of parties. I got to know somebody who sold weed. Then that person started selling coke. Soon people wanted to be around me so we could pick up bags of coke. It became my identity: the guy who’d buy a tray of shots and walk around the bar handing them out, helping pals score weed and coke.

I dropped out of school when I was 17, got my GED, and started working on boats. I was facilitating these experiential education programs, sailing around New England and the Caribbean. At night we’d open a bottle of rum and just throw the lid over the side. Because of the life I grew up in, I didn’t know you put the lid back on a bottle after pouring a drink.

I came ashore in Boston in my early 20s, and my drinking got pretty bad. I’d black out and come to. I’d have to call out off work, and by the time I pieced myself back together, it would be a day later.

“I stayed SOBER through a Friday night so I could go CLIMBING on SATURDAY.”

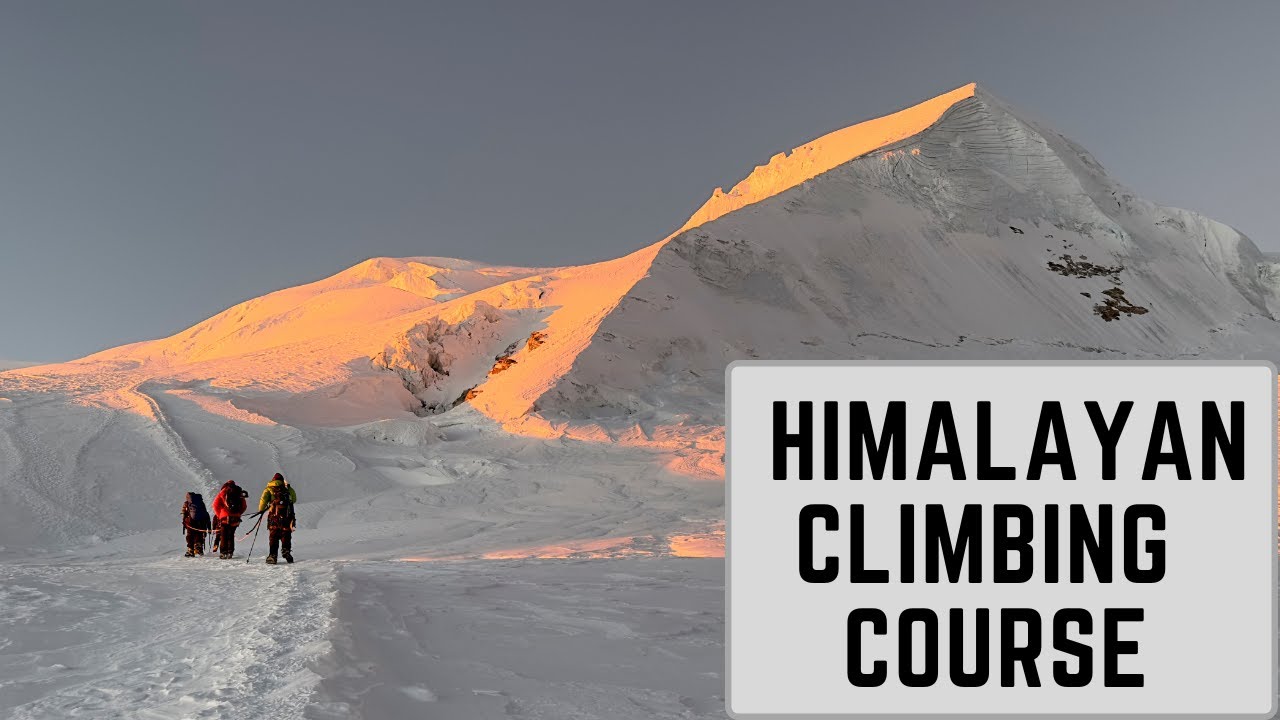

I wanted to change my life but didn’t know how. I was always drawn to the idea of doing something physical and being outdoors, so I went to an outdoor equipment store and bought a GORE-TEX jacket. Walking out, I saw an ice climbing brochure with a guy hanging off this massive ice cliff, and I thought: that’s the craziest thing I’ve ever seen.

I stayed sober through a Friday night so I could go climbing on Saturday. The guide climbed up the cliff effortlessly, and then I struggled my way up. I was sweating. My arms got pumped. I could barely hold on to the ice axes. My shirt was riding up, and my belly was on the ice. It was just like my life, because I was struggling at the time. But a seed was planted, and I thought maybe someday I could climb like him. It gave me something to aspire to, so I’d stay sober on the weekends to climb.

That same