Even as others were dying of COVID-19, Rick Wright made phone calls to his business clients. He lifted weights, did pushups and glided on an elliptical trainer. Late at night, he took his dog on long walks.

“I never felt sick. Not a cough, wheezing, headache. Absolutely nothing,“ said 63-year-old Wright of Redwood City, despite testing positive for the virus – 40 days, straight — after being exposed aboard the Diamond Princess cruise last February.

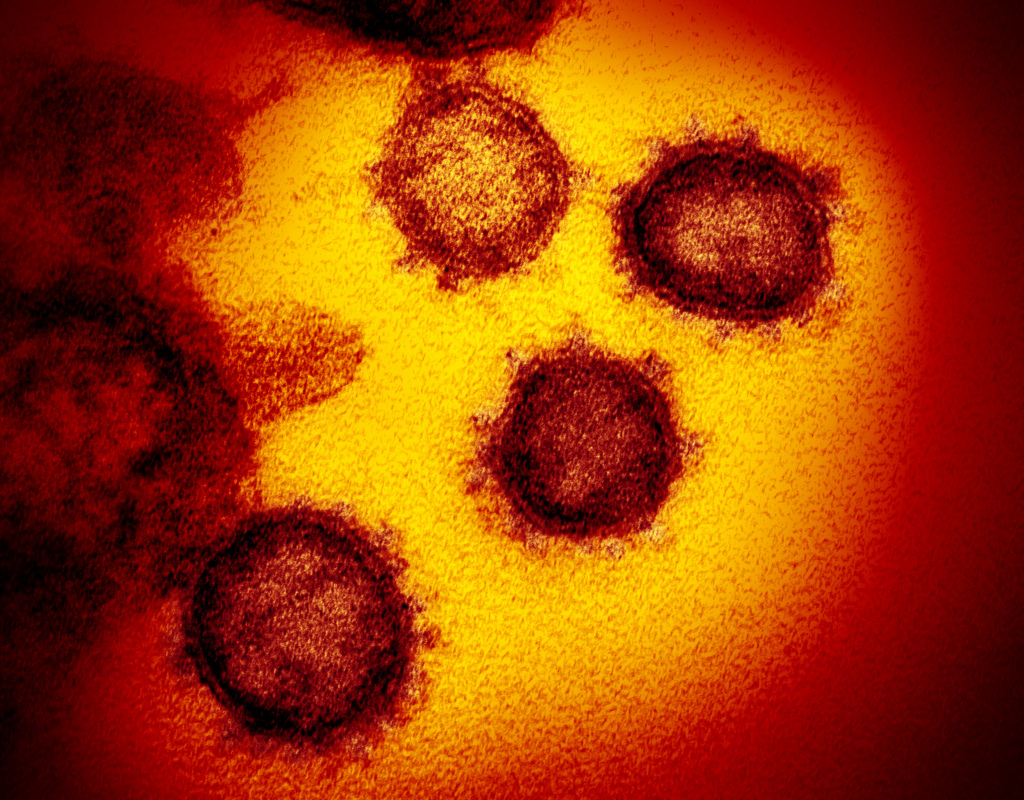

Seven months into a pandemic that has killed more than 667,000 people globally, scientists are searching for clues into why infected people like Wright feel just fine.

Understanding the mystery of their protection may help suggest targets for vaccines and treatment. These cases also underscore the importance of masks and expanded testing, because asymptomatic people may unwittingly transmit infection to others.

The COVID-19 virus seems unprecedented in its spectrum of severity, from innocuous to lethal, said Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Disease.

“Usually a virus that is good enough to kill you would make almost everybody at least a little bit sick,” he said, at this month’s first global COVID-19 Conference.

The nature of the pathogen itself does not seem to explain the person-to-person variability. Among families in the same household, infected by the same virus, people may get profoundly ill — or escape unscathed.

Nor does it seem to matter how much virus is circulating in the body.

Rather, emerging evidence suggests that a person’s immune response, largely influenced by genetics, is what helps determine the severity of illness, say infectious disease experts.

To capture our defenses in action, scientists with a UC San Francisco project are driving their van — outfitted with an exam table and a phlebotomy chair