Brain scans of more than 100 mammalian species, including humans, reveal that the efficiency of information transfer in the brain is the same in all mammals, regardless of size.

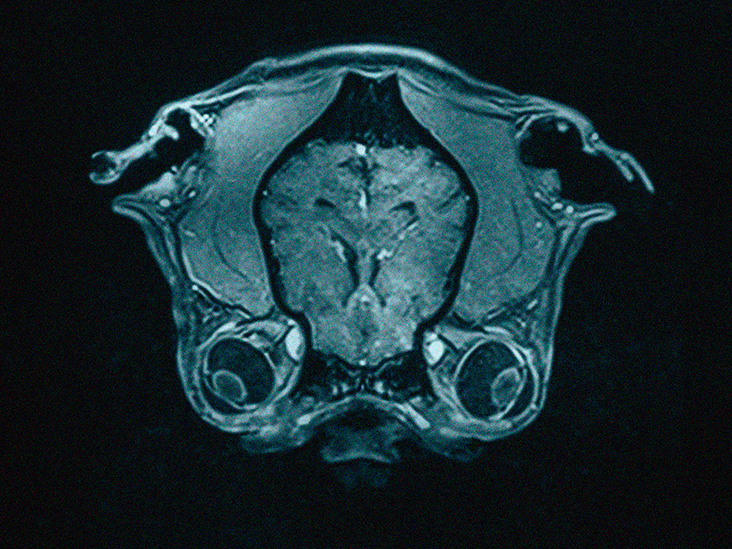

The mammalian brain consists of two sides, or hemispheres, which nerve tracts, also known as axons, connect. The two hemispheres share information along these axons.

How rapidly information spreads in the brain depends on the number of synapses — the junctions between nerve cells — it has to pass through.

An ideal system would have a multitude of long connections to enable the rapid transfer of information between all parts of the brain. However, producing this many neuronal connections comes at a cost to the animal. The evolution of the brain, therefore, represents a compromise.

People commonly believe that human beings, due to our advanced evolution, have higher levels of brain connectivity than other animals, enabling the more efficient and rapid transfer of information throughout the brain.

A new study that researchers from Tel Aviv University in Israel led challenges this assumption. They scanned the brains of more than 120 different mammals and found that brain connectivity is neither higher in humans nor dependent on the size of the brain.

Their findings, which suggest that all mammals have equal levels of brain connectivity, appear in the journal Nature Neuroscience.

The idea that brain connectivity — and, therefore, efficiency — is greater in the human brain has been around for a long time.

“Many scientists have assumed that connectivity in the human brain is significantly higher compared to other an