In late February, executives at Fujifilm’s Tokyo headquarters scrambled to coordinate with a team of 100 employees who would be responsible for a task unprecedented in its 86-year history: Japan’s health minister, Katsunobu Kato, had enlisted the camera and imaging company’s help to fight Covid-19. At that point only some 130 people in the country were infected. But a pandemic was in sight.

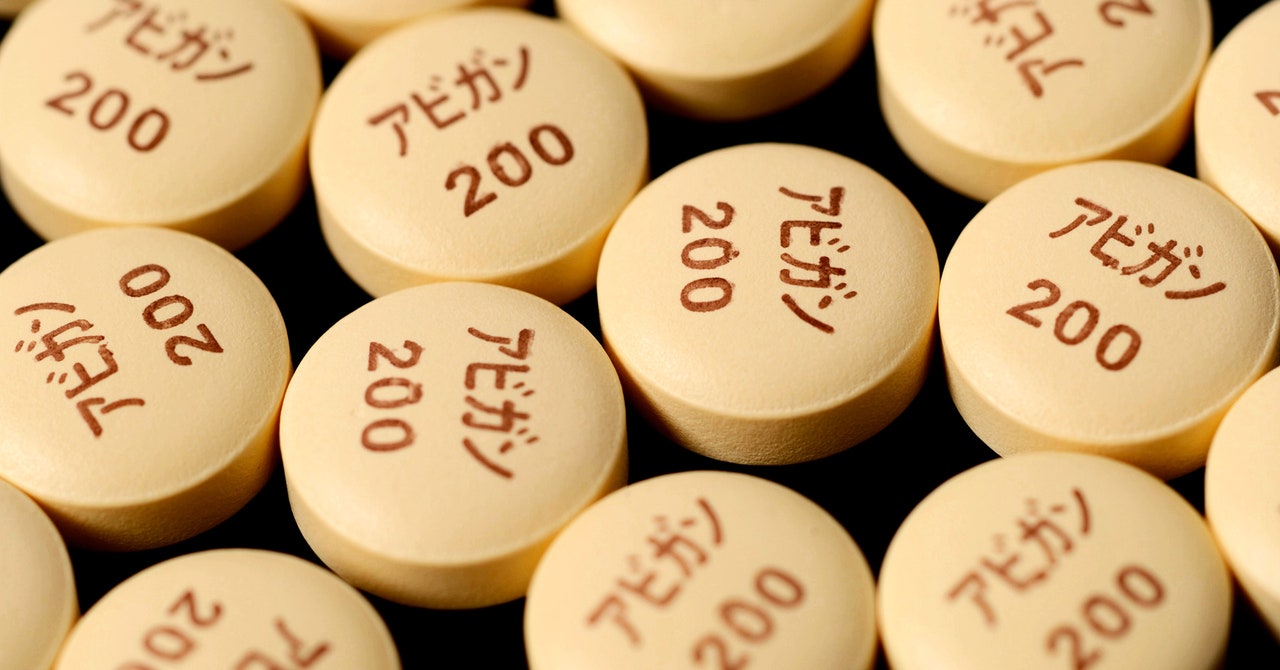

With the outbreak spreading fast and no vaccine or treatment on the horizon, Kato hoped to find an existing drug that could be used to treat the wave of patients that was sure to come. One candidate was an anti-influenza drug called Avigan, which had been developed decades earlier by the Fujifilm subsidiary Toyama Chemical.

In the weeks that followed, the Fujifilm team managed more than some governments could claim to have done in response to the spread of Covid-19: Working from different offices and factories, members of the group made contingency plans for ramping up production of the drug, advised clinical researchers throughout Japan, and helped get the drug to hospitals where its use had been approved by the government as an emergency measure to treat dozens of Covid-19 patients. On March 28—last Saturday—Prime Minister Shinzo Abe told reporters that his government had begun the formal process for designating Avigan as Japan’s standard treatment for Covid-19.

Should I Stop Ordering Packages? (And Other Covid-19 FAQs)

Plus: What it means to “flatten the curve,” and everything else you need to know about the coronavirus.

A critical step in that process involves clinical trials, one of which will conclude at the end of June. And while there is not yet any detailed data supporting Avigan’s effectiveness as a Covid-19 treatment, there are some reasons for optimism. One of them arrived on March 17, when Zhang Xinmin, an official at China’s ministry of science and technology, said that Favipiravir, the generic version of Avigan, had proved to be effective in treating Covid-19 patients at hospitals in Wuhan and Shenzhen.

It was, Zhang said, “very safe and clearly effective” for treating Covid-19 patients. And while the data and methodology behind Zhang’s claims have not been made public, he did announce some of the conclusions doctors had drawn from them: At a hospital in Shenzhen, Zhang claimed Covid-19 patients treated with Favipiravir tested negative for the virus after a median of four days, rather than the 11 days it took for members of the study’s control group to test negative; in another study carried out in Wuhan, patients taking the drug allegedly recovered from fever nearly two days earlier than those who did not take the medication.

Such results, preliminary and unconfirmed as they are, would seem to conform with the way Favipiravir works. Unlike most other influenza treatments, which inhibit the spread of the virus across cells by blocking the enzyme neuraminidase, Favipiravir works by inhibiting the replication of viral genes within infected cells, thereby mitigating the virus’s ability to spread from one cell to another.

What this means, in practical terms, is that patients who take the dr