It’s 2: 00am. I’m in bed and fast asleep. Suddenly, at full volume, every phone in the house begins blaring a heart-jolting siren.

It’s three piercing blasts of an alarm, and then a woman’s calm voice repeats one word: “earthquake”.

There’s no time to think — just act.

I throw off the covers, my wife grabs our son and we duck under a table.

This isn’t a drill. The alerts are a warning that a strong earthquake is about to hit.

Every time I get one on my phone, I think: ‘is this the big one? Day X?’

That’s the major earthquake with a 70 per cent probability of striking Tokyo some time in the next 30 years.

I wait. Will this time just be a rumble? Or the highest level on the Japanese seismic intensity scale: Shindo 7?

That’s where it’s impossible to remain standing or move without crawling. The earth shakes so much people may be thrown through the air.

Waiting under the table with my heart beating wildly, I feel a slight sway in my building — it’s only a Shindo 3.

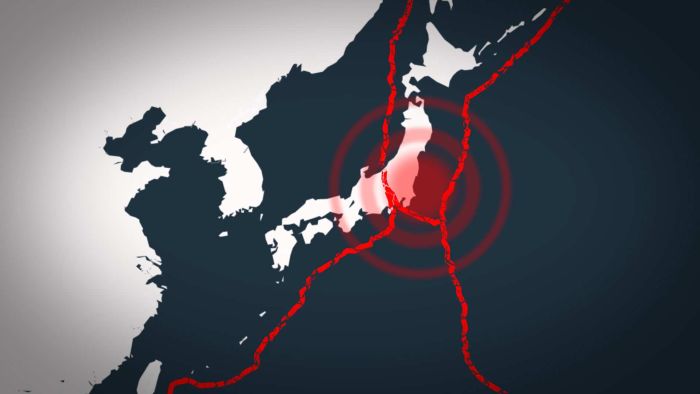

Japan straddles four tectonic plates

I’ve experienced a few of these alerts in the past few years — and thankfully it’s always been the alert itself that’s the greatest shock.

Loading…

It can ring out over loudspeakers on train platforms and interrupt radio stations.

But living with this risk is a reality of life in Japan, which lies on the Pacific ring of fire, an incredibly seismically active area.

The country occupies the intersection of four tectonic plates. The result has been events of unimaginable horror and carnage.

The Meiji-Sanriku earthquake of 1896 was barely felt by the residents along the coast of Tohoku, but moments later a huge tsunami the size of an 11-storey building roared in.

And in 1923, the Great Kanto Earthquake is believed to have shook Tokyo and Yokohama for as long as 10 minutes.

The powerful quake then triggered a 12-metre high tsunami. People who fled to an abandoned lot in downtown Tokyo were burned to death by a fire tornado.

More than 140,000 people were killed.

More recently, the March 2011 triple d