This is the unusual legend of how researchers went to some of the deepest, darkest depths of the ocean, dug 250 feet down into the sediment, gathered an ancient neighborhood of microbes, brought them back to a laboratory, and restored them. And you’re going to believe: Why, in the already-horrible year of 2020, would they lure fate like this? Well, it turns out that not just is everything OK, but that whatever is in reality very, very exceptional– at least far away from mankind in the deep-sea muck of the world’s oceans.

This story starts more than 100 million years earlier in the middle of what we humans now call the Pacific Ocean. Volcanic rock had actually formed a hard “basement” of seafloor, as geologists call it. Over this, sediment started to collect. But not the kind of sediment you might expect.

In other places on the planet’s oceans, much of the seafloor sediment is organic matter. Dead animals, from the tiniest plankton to the biggest whales, pass away, sink, and form a filth that scavengers hoover up and excrete. The western coasts of the Americas are a timeless example: Upwelling currents bring nutrients from the deep, which feed all kinds of organisms nearer the surface area, which in turn feed larger animals, and on up the food chain. Whatever ultimately passes away and wanders down to the bottom, where the detritus ends up being food for bottom-dwelling animals. The seas are so jam-packed with life, they’re downright murky. (Believe, for instance, of California’s hyper-productive Monterey Bay.) Organic matter builds up so fast on the seafloor, much of it gets buried under still more layers of raw material prior to the scavengers can get to it.

The sediment core samples

Thanks To IODP JRSOBy contrast, in the middle of the Pacific, there’s certainly life, just a lot less of it. Appropriately, the water away the coasts of Australia and New Zealand is among the clearest in the world. There’s no upwelling and much less life at the surface, a lot less raw material is sinking to the seafloor to form sediment. What little does sink is instantly hoovered up by limited bottom-dwellers like sea cucumbers.

” It’s the least-explored big biome on Earth, since it covers 70 percent of Earth’s surface area,” says Steven D’Hondt, who co-led the exploration and coauthored a brand-new paper in Nature Communications describing the findings. “And we understand so little about it.”

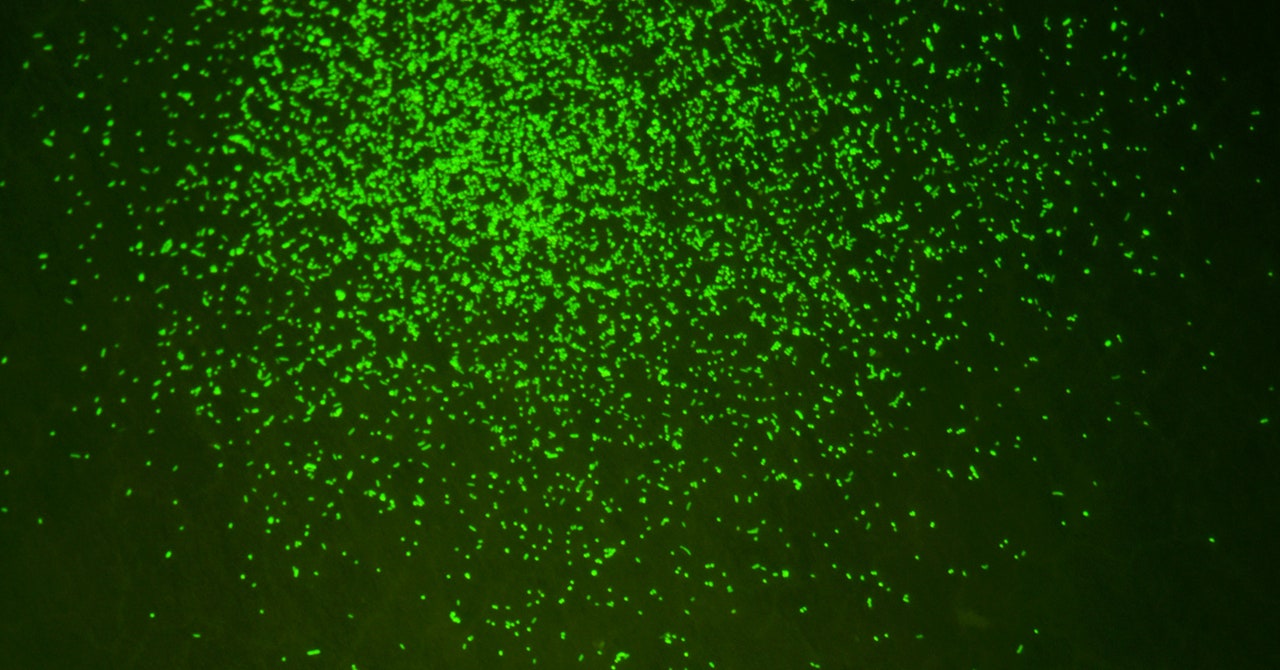

Dropping drills as much as 19,000 feet deep some 1,400 miles northeast of New Zealand, D’Hondt and his colleagues were on a mission to probe these ancient deep-sea sediments for life. Much of the seafloor could be volcanic ash blown from the land, along with metal bits from space. “There’s a measurable fraction of it that’s cosmic particles,” says D’Hondt. “If you trawl through the shallow clay with a magnet, you’ll take out micrometeorites.”

Even at the surface of t