‘News coverage of the crisis amplified the flag’s fame as not only an Indigenous symbol of unity but of resistance’

By Jessica Deer, CBC News

July 11, 2020

Thirty years ago, images of warriors clad in camouflage and bandanas, wielding guns and bright red-and-yellow flags were plastered across newspapers and television broadcasts throughout the Oka Crisis.

The 78-day standoff that began on July 11, 1990, between the Kanien’kehà:ka (Mohawk) community of Kanesatake, the Sûréte du Québec provincial police and, later, the Canadian military was over a contested area of land known as the Pines northwest of Montreal. In solidarity, the Kanien’kehà:ka community of Kahnawake blocked the Honoré Mercier Bridge that connects the South Shore to the island of Montreal.

The Kanien’kehà:ka and their fight for human rights was put on the Canadian and international stage that summer, and so was Karoniaktajeh Louis Hall’s warrior flag.

Karoniaktajeh Louis Hall and some of his paintings in 1969. (Submitted by Louise Leclaire)

“The flag was zeroed-in on by the media,” said Teiowí:sonte Thomas Deer, communications co-ordinator for the Kanien’kehà:ka Nation Office in Kahnawake.

“News coverage of the crisis amplified the flag’s fame as not only an Indigenous symbol of unity but of resistance. From that point on, other Onkwehón:we [Indigenous] Peoples began using this flag as they resisted colonial oppression.”

Two masked Mohawk Warriors remove a flag from the main barricade at Oka, Que., September 1, 1990, in order to keep it from falling into the hands of Canadian army. (Tom Hanson/The Canadian Press)

Who was Karoniaktajeh Louis Hall?

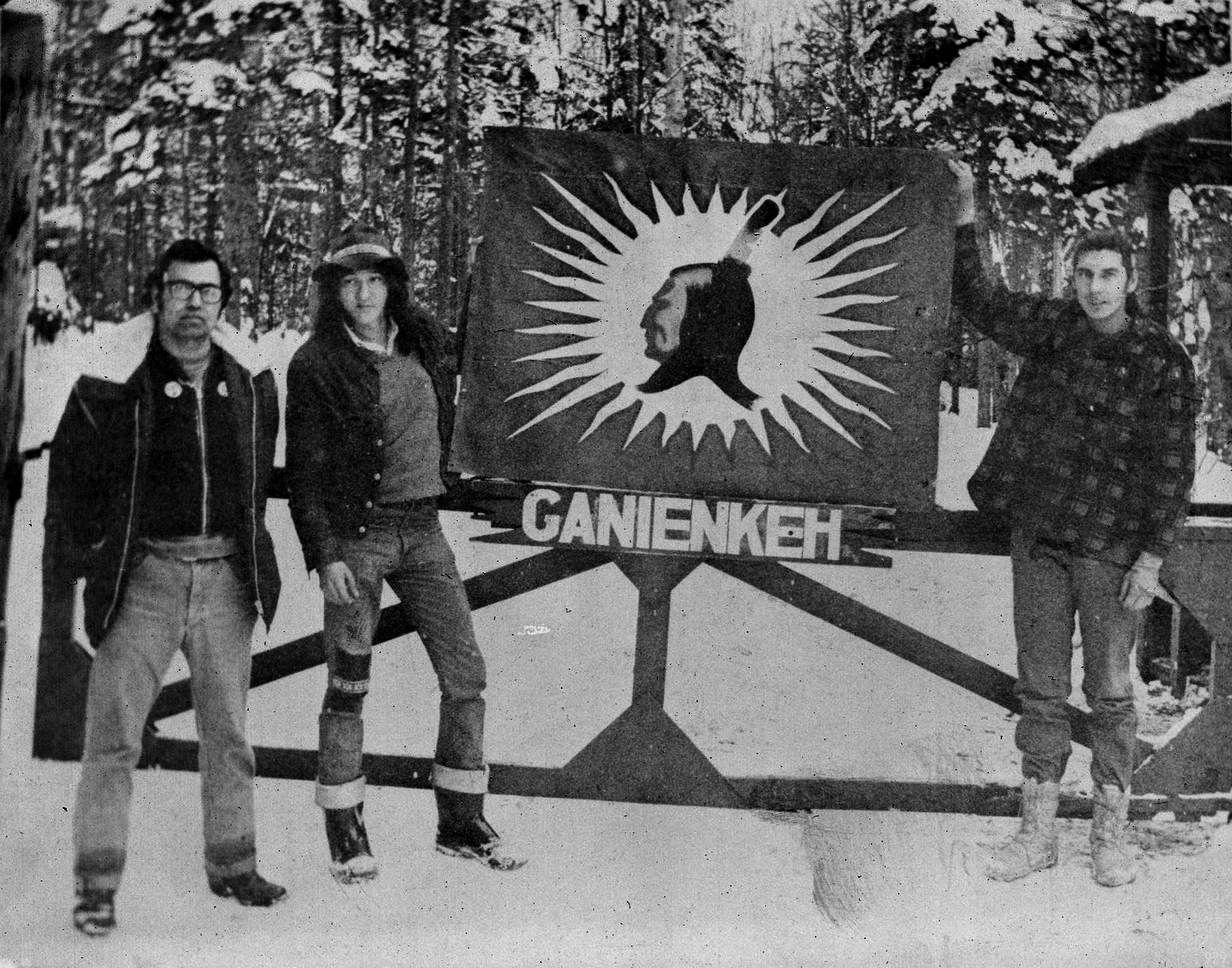

Hall, who died in 1993 at the age of 75, was an activist, writer and artist from Kahnawake. He first created the flag during the repossession of Ganienkeh in 1974, when he and others went into the Adirondack Mountains to create a new settlement in upstate New York.

Dubbed the “unity flag” or “Indian flag,” it depicted a long-haired Indigenous man over a sunburst atop a red banner, and was intended as a symbol for all Indigenous people to stand behind.

The Kanien’kehá:ka Onkwawén:na Raotitióhkwa Language and Cultural Center in Kahnawake, Que., has in its archives this 1974 photo of Hall’s original flag in Ganienkeh. (Submitted by Kanien’kehá:ka Onkwawén:na Raotitióhkwa Language and Cultural Center)

In the 1980s, Hall made a new version of the flag, replacing the long-haired man with a Kanien’kehá:ka warrior. It was designed specifically for the Rotisken’rakéhte, or Mohawk Warrior Society, serving as a symbol for the traditional vanguard of the Kanien’kehá:ka Nation when carrying out their duties for the people.

That version of the flag is the one most recognizable today; it has been mass produced on flags, clothing, key chains, stickers and decals.

Louise Leclaire and her uncle Karoniaktajeh Louis Hall in 1993. (Submitted by Louise Leclaire)

“That was what he wanted,” said Louise Leclaire, Hall’s niece and closest surviving relative, about the flag being used everywhere.

“He loved his people, and he wanted to make sure Indians deserved their traditions, language, and just to have pride in who they are.”

An activation of pride

In 2019, several large-scale flags were hung off the Honoré Mercier Bridge in Kahnawake, Que., to commemorate the 29th anniversary of the Oka Crisis. (Submitted by Deidre Diome)

Kahente Horn-Miller, an associate professor at Carleton University in Ottawa and the school’s assistant vice-president of Indigenous initiatives, said the flag became an active part of Kanien’kehá:ka communicating their identity.

“What Karoniaktajeh was trying to do is activate that sense of pride in who we are,” she said.

In 2010, she published “From Paintings to Power,” an academic article about the flag, in the Journal of the Society for Socialist Studies.

The flag is often misrepresented, she said. Negative connotations were placed on it because of how the Oka Cr