Requiring all departments to do a detailed cybersecurity analysis would help address the reality that while digital government has big potential benefits, it also paints a bigger target on Canada’s aging federal IT systems, writes Alexander Rudolph.

This column is an opinion by Alexander Rudolph, a PhD student in the Department of Political Science at Carleton University where he researches cyberdefence and cyberwarfare. Outside of his research, he also works as an independent consultant and policy analyst. For more information about CBC’s Opinion section, please see the FAQ.

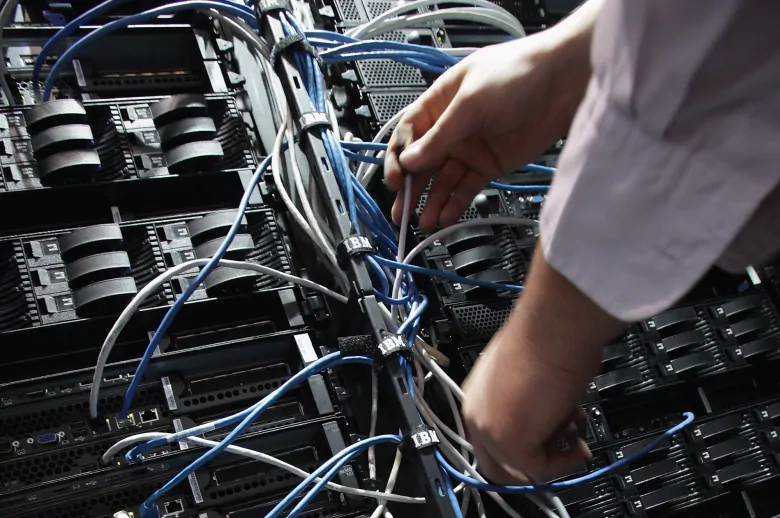

Official documents recently obtained by The Canadian Press describe “mission-critical” Government of Canada computer systems and applications as “rusting out and at risk of failure.” Such statements are alarming for a host of reasons, particularly when considering the potential loss of critical systems that support the nation’s social services.

However, while these systems are integral to providing digital services, there does not appear to be an urgent acknowledgement of the security risks these old systems also pose.

While the Government of Canada released a National Cyber Security Strategy in 2016, it expresses little concern for the specific threats posed by legacy systems. The strategy also offers few concrete plans in terms of what the government will do to achieve its stated goals.

In an article about the government’s aging IT infrastructure, Andre Leduc, vice-president of government relations and policy with the Information Technology Association of Canada, says that many officials didn’t seek to upgrade these old systems because they still worked. That approach seems to be based on the adage that “if it isn’t broken, don’t fix it.”

But at least as worrying as a potential failure of these archaic systems is the risk that government and public information could be stolen, or hijacked and held hostage.

A recent 800-page federal government response to an order paper question filed by Conservative MP Dean Allison reveals that federal departments or agencies mishandled personal information belonging to at least 144,000 Canadians over the past two years alone, a figure that includes incidents ranging from misdirected mail to technology-related breaches. And as Canada moves towards “digital government” while relying on decaying infrastructure, the risks are likely to increase.

Using old technology is commonplace in both the government and private sectors due to the costs associated with upgrading. However, in a 21st-century security environment, these systems are ticking bombs.

Old systems are vulnerable largely due to a loss of technical support by developers, which dramatically increases the chance of a successful attack.

As new systems and applications are created, developers phase out support for older ones — and we’re not just talking about decades-old mainframes. Microsoft ended support for its Windows 7 operating system on Jan. 15, for example, which means the company won’t provide any new security updates. This creates significant security risks for these systems and the applications running on them, as they become more prone to malware and hacking.

Ransomware-based cyberattacks, which can lock down computers until a ransom is paid, are just one type of exploit being used by criminals and countries alike. In October last year, the Canadian Centre For Cyber Security issued a warning about ransomware called Ryuk that it said was, “affecting multiple entities, including municipal governments and public health and safety org