P ERHAPS MORE than any other, cancer is seen as an illness of genes gone wrong. So, as genetic-sequencing innovation has actually ended up being cheaper and faster, cancer researchers are utilizing it to inspect which changes to genes trigger tumours to spread.

The current insights from one group, the global Pan-Cancer Analysis of Entire Genomes ( PCAWG), are revealed today in Nature In an analysis of the complete genomes of 2,658 samples of 38 kinds of tumour drawn from the bladder to the brain, the scientists give a blow-by-blow account of how a series of hereditary anomalies can turn normal cells into runaway clones. It offers the most comprehensive analysis yet of where to find this damaging interruption to DNA and, by unpicking the genes of what makes cancer tick, just how tough it will be to tame.

For each of the cancer samples, the group produced a read-out of the tumour genome– the 3bn or so specific DNA letters– and compared it with the genome sequences of healthy cells drawn from the same clients. In this way they might look for the hereditary signatures of the cancer cells, where specific anomalies had deformed the hereditary information.

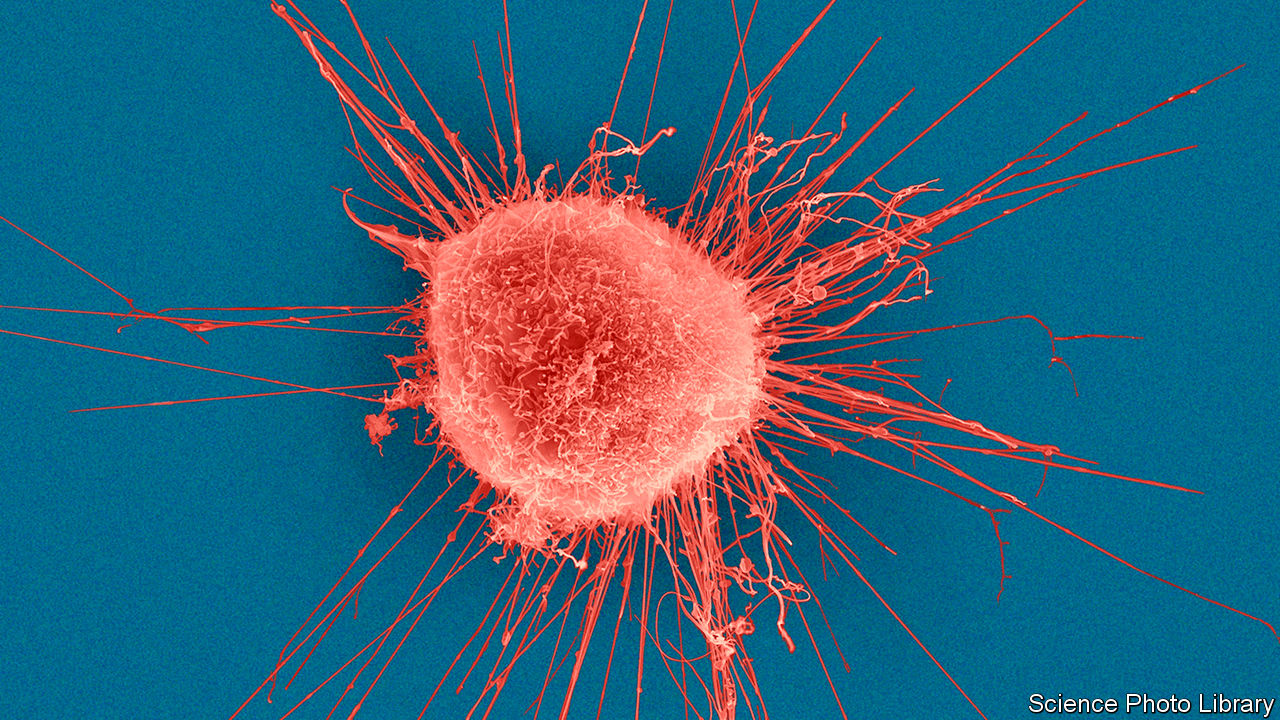

A lot of anomalies in the genome are safe. Motorist mutations, where hereditary modifications trigger a cell to multiply more easily and faster than other cells, can set off tumour growth. Lots of driver mutations have actually been found over the past decade and a handful have actually been translated into brand-new medicines. In a fifth of breast cancers (pictured), for example, a motorist anomaly in the gene HER 2 makes cells produce more of a protein on their surface area that motivates them t