In March, when cherry blossoms are beginning to bloom, the Japanese leg of the Olympic Torch relay will kick off at a soccer stadium 12 miles from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. A nearby sports complex will also host the Games’ baseball and softball matches. That’s bound to surprise and maybe worry some attendees, whose memory of the power plant’s catastrophic meltdown nine years ago is still fresh. But in fact, the government has been aggressively decontaminating and rehabilitating Fukushima prefecture, and life is slowly returning to the exclusion zone.

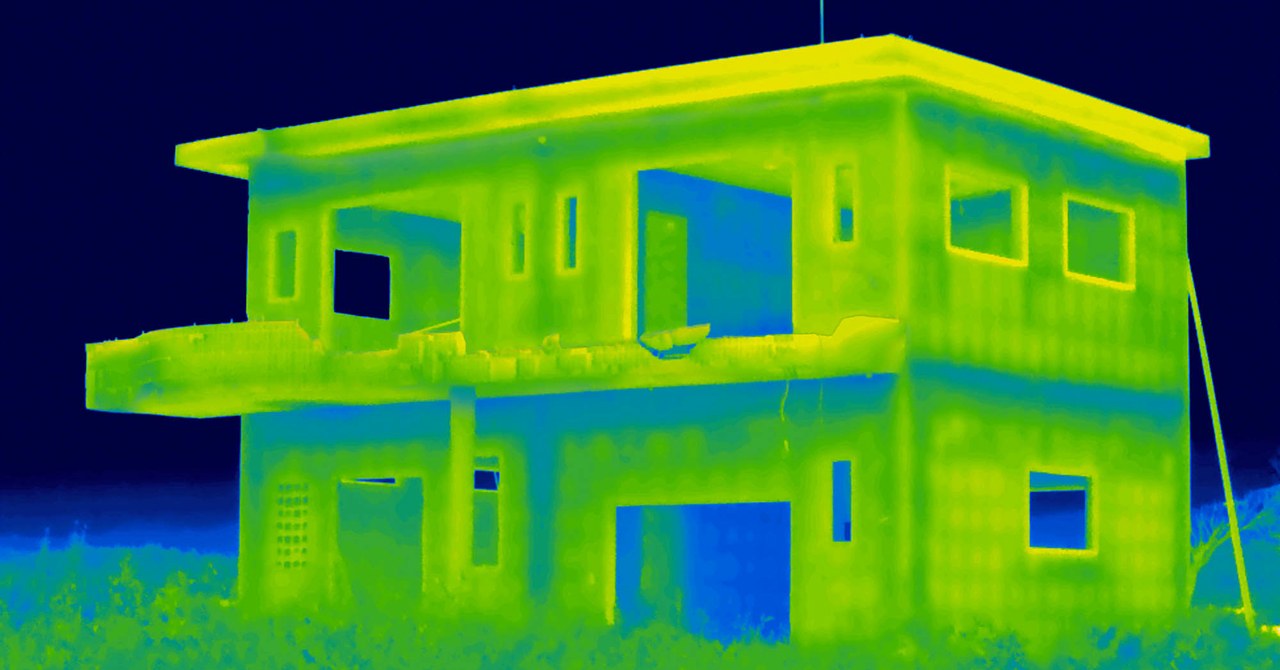

Giles Price explores this eerie transformation in his new book, Restricted Residence, documenting construction workers, office drones, and even a taxi driver who the government pays to roam the half-deserted streets, since customers are still few. “There are these little pockets of people getting on with life again,” Price says. “You have a house that’s been rebuilt next to a house that’s still dilapidated with weeds growing out of it.”

The magnitude-9.0 Great East Japan Earthquake, as it’s referred to there, struck the country’s northeast coast on March 11, 2011, triggering a tsunami that breached the sea wall and cut all power to the plant. Fuel melted in three reactors, releasing 940 petabecquerels of radioactive particles—enough to give everyone on earth a free X-ray. In the aftermath, more than 100,000 people fled a 12-mile radius around the plant.

Japan has since poured $27 billion into cleaning up the mess. Some 75,000 workers have scrubbed down roads, walls, roofs, gutters, and drain pipes. They have stripped the landscape of 600 million cubic feet of grass, trees, and topsoil and stuffed it into millions of black tarp