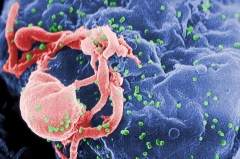

Image of HIV. Credit: CDC/ C. Goldsmith, P. Feorino, E. L. Palmer, W. R. McManus New research study exposes why comorbidities continue individuals coping with HIV, in spite of reducing the infection through treatment. Individuals coping with HIV frequently experience persistent swelling, despite the fact that antiretroviral treatment has actually made HIV a workable illness. This can put them at an increased threat of establishing comorbidities such as heart disease and neurocognitive dysfunction, which can make a considerable effect on the durability and quality of their lives. Now, a brand-new research study released in the journal Cell Reports on November 14 describes why persistent swelling might be occurring and how suppression and even elimination of HIV in the body might not fix it. “This research study highlights the significance of doctors and clients acknowledging that reducing and even removing HIV does not remove the danger of these unsafe comorbidities.”– Michael Bukrinsky In the research study, researchers from the George Washington University show how an HIV protein completely modifies immune cells in a manner that triggers them to overreact to other pathogens. When the protein is presented to immune cells, the scientists discovered that genes in those cells related to swelling turn on, or end up being revealed. These pro-inflammatory genes stay revealed, even when the HIV protein is no longer in the cells. This “immunologic memory” of the initial HIV infection is why individuals coping with HIV are prone to extended swelling, putting them at higher threat for establishing heart disease and other comorbidities, according to the scientists. “This research study highlights the value of doctors and clients acknowledging that reducing or perhaps getting rid of HIV does not get rid of the danger of these unsafe comorbidities,” Michael Bukrinsky, teacher of microbiology, immunology, and tropical medication at GW’s School of Medicine and Health Science and lead author on the research study, stated. “Patients and their physicians need to still go over methods to decrease swelling and scientists need to continue pursuing prospective healing targets that can decrease swelling and co-morbidities in HIV-infected clients.” For the research study, the research study group separated human immune cells in vitro and exposed them to the HIV protein Nef. The quantity of Nef presented to the cells resembles the quantity discovered in about half of HIV-infected individuals taking antiretrovirals whose HIV load is undetected. After a time period, the scientists presented a bacterial toxic substance to produce an immune action from the Nef-exposed cells. Compared to cells that were not exposed to the HIV protein, the Nef-exposed cells produced a raised level of inflammatory proteins, called cytokines. When the group compared the genes of the Nef-exposed cells with the genes of the cells not exposed to Nef, they recognized pro-inflammatory genes that remained in a ready-to-be-expressed status as an outcome of the Nef direct exposure. These findings might assist discuss why particular comorbidities continue following other viral infections, consisting of COVID-19, Bukrinsky stated. “We’ve seen this pro-inflammatory immunologic memory reported with other pathogenic representatives and frequently described as ‘qualified resistance,'” Bukrinsky describes. “While this ‘skilled resistance’ progressed as an useful immune procedure to safeguard versus brand-new infections, in particular cases it might cause pathological results. The supreme impact depends upon the length of this memory, and extended memory might underlie long-lived inflammatory conditions like we see in HIV infection or long COVID.” Recommendation: “Extracellular blisters bring HIV-1 Nef cause long-lasting hyperreactivity of myeloid cells” by Larisa Dubrovsky, Beda Brichacek, N.M. Prashant, Tatiana Pushkarsky, Nigora Mukhamedova, Andrew J. Fleetwood, Yangsong Xu, Dragana Dragoljevic, Michael Fitzgerald, Anelia Horvath, Andrew J. Murphy, Dmitri Sviridov and Michael I. Bukrinsky, 14 November 2022, Cell Reports. DOI: 10.1016/ j.celrep.2022111674 The National Institute of Health’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute supported this research study.

Read More

Why Comorbidities Persist: HIV Infection Leaves a “Memory” in Cells