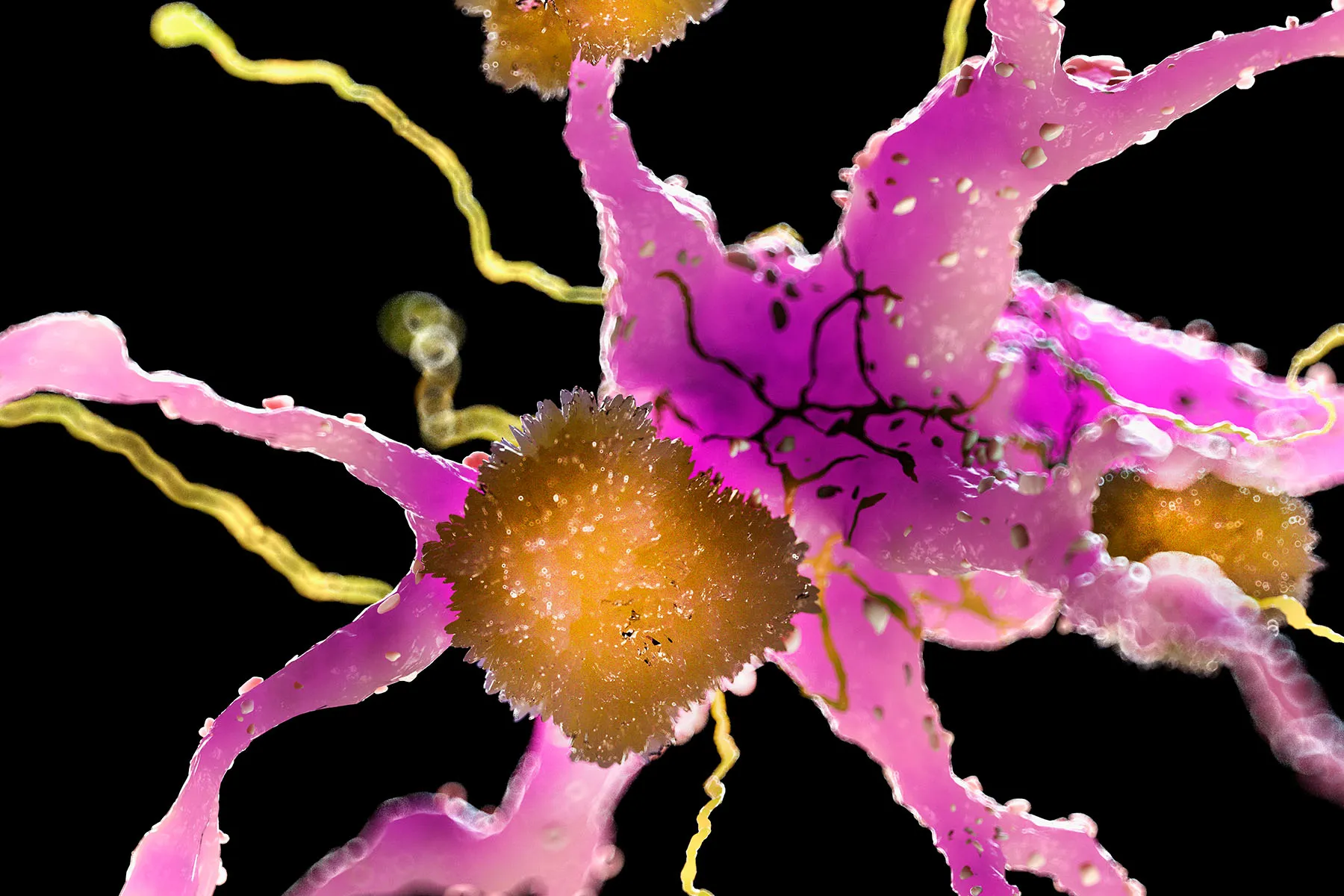

In November of 1901, a young German psychiatrist and neuroanatomist, Alois Alzheimer, discovered what seemed misfolded proteins forming sticky clumps, or plaques, in between the nerve cells in the brain tissue of a client who had actually passed away from dementia. Inside the nerve cells he discovered threadlike twists, called neurofibrillary tangles, of another protein. Ultimately these plaques and tangles pertained to specify the illness called after him: Alzheimer’s illness.

By the mid 1980s, these unusual proteins had actually been determined as beta-amyloid proteins, and by the 1990s it was commonly accepted that an excess of these proteins triggered the development of the plaques, which in turn triggered the illness. The tangles, which ended up being malformed hairs of a protein called tau, were believed to be an outcome of the amyloid plaques. For the previous 30 years, the bulk of research study on Alzheimer’s, and the majority of the efforts to discover a treatment, have actually been based upon the amyloid hypothesis.

After years of research study based on this hypothesis, drug trials have actually primarily struck out. No drug checked has actually produced significant enhancement in the signs of the illness. Even drugs that lower amyloid levels in the brain have not done what actually matters: enhance the lives of individuals with Alzheimer’s illness.

In January of this year, a brand-new Alzheimer’s drug, lecanemab, was authorized by the FDA even after the deaths of numerous trial individuals raised concerns about the drug’s security. Security concerns aside, lecanemab is far from a remedy. It did not stop the development of the illness, and it decreased cognitive decrease by just a percentage. “It’s a little action in the best instructions,” states Donald Weaver, MD, PhD, scientific neurologist and Alzheimer’s scientist at the University of Toronto, “not a huge stride.”

Are We in a Rut?

These frustrating outcomes have actually led lots of scientists to ask if the amyloid hypothesis requires reconsidering. Marissa Natelson Love, MD, is a neurology scientist at the Heersink School of Medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Natelson Love has actually focused her research study on anti-amyloid treatments based upon the amyloid hypothesis and is hiring clients for additional research studies on lecanemab. Still, she states, “Every time we have a conference, somebody asks, ‘Are we on the incorrect track?'” Maybe, as Weaver as soon as put it, Alzheimer’s research study remains in an “intellectual rut.”

There’s a factor science in some cases gets in these ruts. Science is a sluggish, accretive procedure that builds on work– frequently years of work– that came in the past.

Scientist total PhDs on a specific subject, then go on to be postdocs in the laboratory of a recognized researcher in the very same location. Quickly there’s a whole body of scientists with years of training and experience in one technique to a provided issue, discusses Michael Strevens, PhD, thinker of science at New York University. “There’s a procedure, what you may call a dish book, for doing the science. Whereas with a brand-new, untried hypothesis, nobody has actually yet composed the dish book.” This isn’t laziness, however momentum. Like a huge ocean liner, research study can’t turn on a penny. When it concerns Alzheimer’s, the momentum is primarily behind the amyloid hypothesis. The functions of other procedures in the course of the illness, such as swelling, prior infections, or autoimmune health problem, have actually gotten brief shrift.

Still, we should not toss the child out with the bathwater. The issue might not be with the amyloid hypothesis, however with the particular drugs being checked. Possibly scientists simply have not discovered the best drug. Or possibly these are the best drugs and they’re simply being offered at the incorrect time; it might be that in order to succeed, anti-amyloid treatments require to begin long prior to signs appear.

Another possibility is that the choice of tri